Earlier this month, the University published its second annual report of progress made toward the goals established in its diversity and inclusion action plan. Released in February 2016, the DIAP aims to increase representation of historically underrepresented groups on campus, strengthen research and teaching on diversity and inclusion issues and improve campus life.

Though the University released the 2015-16 report at the beginning of the spring 2017, the 2016-2017 report was released May 16 to facilitate “an evaluation of a full year of progress” and allow the “Diversity and Inclusion Oversight Board … ample time to review and give feedback on the draft of the report,” wrote Shontay Delalue, vice president of the Office of Institutional Diversity and Equity, in a community-wide email. The DIOB’s review of the second annual DIAP report is scheduled to be released in the coming weeks, according to the email.

The annual report highlights efforts to promote diversity and inclusion across all aspects of campus life, including University admissions and hiring, as well as the University’s relationship with the greater Providence community. Following suggestions outlined in last year’s DIOB review, this year’s report also includes a fundraising update, a section discussing progress made in disability inclusion and new accountability mechanisms for departmental DIAPs.

Fundraising update

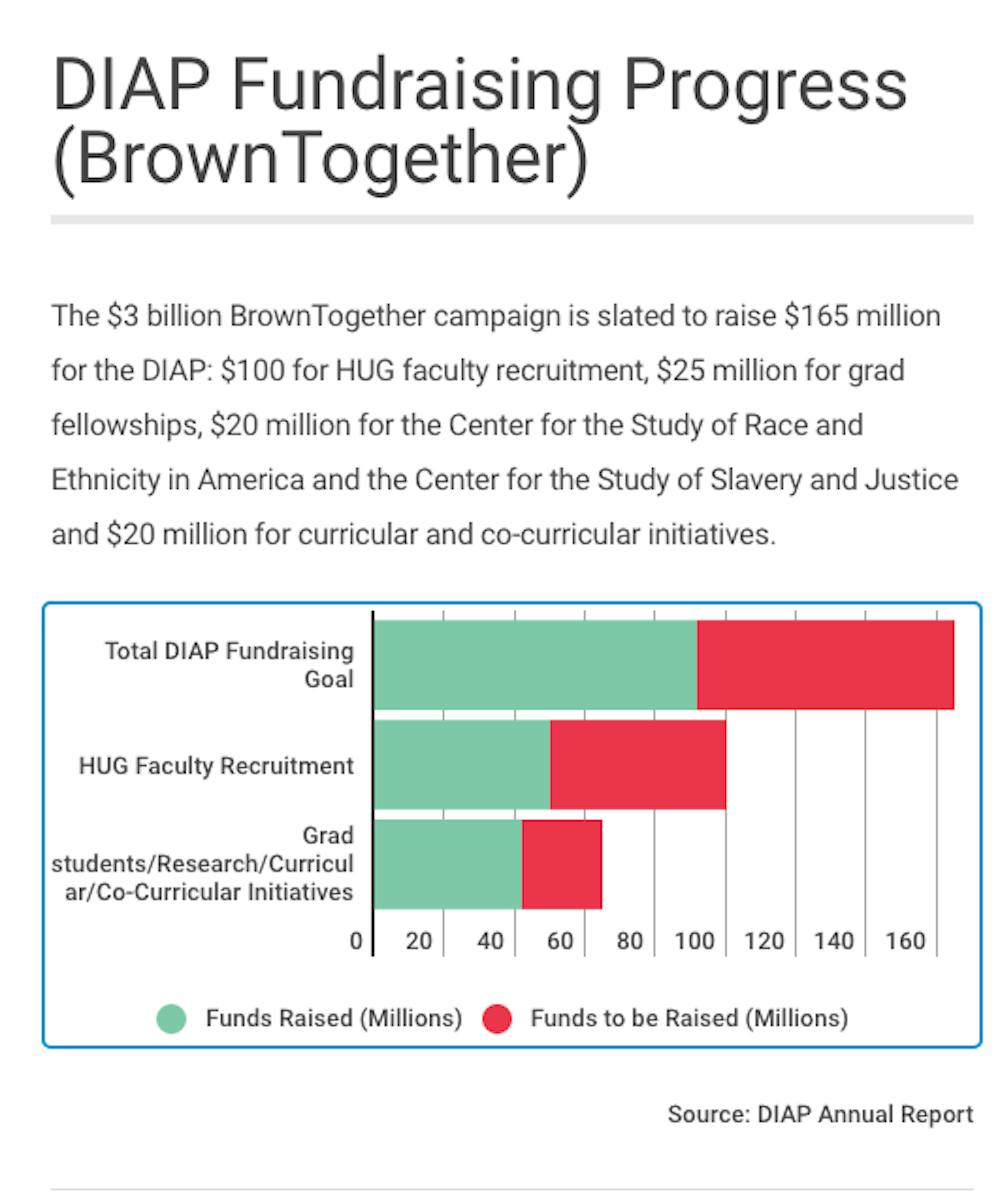

The $3 billion BrownTogether campaign is slated to raise $165 million for DIAP initiatives. To date, the University raised $50 million to hire faculty from historically underrepresented groups, defined by the DIAP as individuals who self-identify as “American Indian, Alaskan Native, African American, Hispanic or Latinx and Native Hawaiian and/or Pacific Islander.” The University aims to raise $100 million in total to double the number of HUG faculty members by 2022, which would necessitate hiring at least 60 faculty members, The Herald previously reported.

To date, the University has also raised $41.7 million to fund initiatives that support goals established in the DIAP such as “diversifying the graduate student population; expanding research centers focused on issues of race, ethnicity and social justice; and supporting curricular and co-curricular initiatives that promote diversity and inclusion,” Delalue wrote.

The University previously set goals to raise $25 million for grad fellowships and $20 million for the Center for the Study of Race and Ethnicity in America and the Center for the Study of Slavery and Justice, as well as $20 million for “curricular and co-curricular initiatives that promote diversity and inclusion,” according to the DIAP. In an email to The Herald, Delalue wrote that “a majority of the $41.7 million raised has gone to curricular and co-curricular programs, and we will continue to look to raise funds in support of the other major areas.”

President Christina Paxson P’19 and Provost Richard Locke P’18 collectively gave $7.1 million from their flexible funds to support initiatives such as the Presidential Diversity Postdoctoral Fellowships and the Provost’s Visiting Professor Program.

University progress in recruiting and retaining HUG faculty and staff

The annual report provides data on the numbers of staff, students and faculty members from historically underrepresented groups from fall 2013 through fall 2017.

Notably, the Office of Residential Life experienced a “dramatic shift in compositional diversity,” as “six of the last seven hires were staff of color (four from HUGs),” according to the report. The University has also invested in the retention of HUG staff; for instance, Brown Dining Services recently “created a position to specifically address issues related to diversity and inclusion.”

Since 2015, the University has also consistently increased the number of HUG faculty holding positions of professor, associate professor, assistant professor or senior lecturer, according to the report.

The report highlighted the success of the Presidential Diversity Postdoctoral Fellowships in placing fellows into tenure-track positions. Four of the six fellows from the 2016-18 cohort and seven of the eight fellows from the 2015-17 cohort obtained tenure-track positions — with two transitioning into tenure-track positions at Brown.

Kevin Escudero, assistant professor of American and ethnic studies, said he applied to the program because he wanted to join a community of individuals who “were making that transition from PhD program into being a faculty or a post-PhD individual.”

“In grad school, we learn how to do research, we learn about the research process, about writing our dissertations,” he wrote in a follow-up email to The Herald. “But we don’t learn about what the responsibilities of a faculty member are” or how to balance them, he added.

Escudero said the fellowship program prepared him for his tenure-track position as it allowed him to “teach a course, work on turning my dissertation into a book.” In addition, the fellowship allowed Escudero to be mentored by “faculty at Brown and also … (have) the opportunity to mentor current undergraduate students.”

In the future, Escudero said he hopes the University will “prioritize and encourage departments that haven’t had the opportunity” to host fellows to do so in an effort to ensure that as “discussions of diversity are happening, they’re happening across all different parts of campus — not just in particular spaces or departments.”

Representation of HUG undergraduate and graduate students

Last fall, HUG students comprised 20 percent of the Graduate School’s incoming class. Eleven percent of the graduate student body currently identifies as belonging to a HUG, according to the report.

This represents a significant increase from the year 2014-2015, when 8.8 percent of graduate students identified as belonging to a HUG, according to the DIAP. The Grad School aims to double this percentage of HUG students by 2022, according to the DIAP.

In her email to The Herald, Delalue wrote that she attributes the Grad School’s success to the school “working collaboratively with academic departments to rethink the recruiting and admission process.”

Additionally, the Grad School put “careful thought … into ensuring that HUG graduate students had a welcoming experience and access to resources once on campus. This was achieved through another collaborative effort between the Graduate School and the Brown Center for Students of Color,” she wrote.

The report also provided information on undergraduate enrollment from HUGs over the past five years. Relative to total enrollment, 2017 saw “a slight decrease in undergraduate students from HUGs,” according to the report. In fall 2017, 6.4 percent of enrolled undergraduates identified as black or African American, 11.5 percent identified as Hispanic or Latino, 0.4 percent identified as American Indian or Alaska Native and 0.2 percent identified as Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, according to the report. From 2014 to 2016, HUG enrollment hovered slightly above 21 percent.

Beyond the University’s definition of historical underrepresentation

The release of the DIAP provoked conversations on the University’s accessibility for individuals belonging to groups that might not be considered historically underrepresented by the plan. In her email to The Herald, Delalue wrote that “while the DIAP outlined a specific set of historically underrepresented groups that have had limited participation in higher education to date, this does not confine us in our ability to discuss various diversity-related topics above and beyond the plan.”

For instance, the report includes data on the number of women faculty in STEM and Asian faculty in the humanities and social sciences.

Additionally, last year, the DIOB recommended the University conduct “a campus-wide survey of the built environment of Brown, with a focus on accessibility for the wide range of disabled persons in our community,” according to a copy of the DIOB memo.

Though it has yet to implement such a survey, “the University (has taken) a number of early steps to ensure greater attention to factors that impact the full participation of individuals with disabilities,” Delalue wrote. “Significant progress has been made on the physical accessibility of buildings across campus (but) additional work remains.”

Citing the ongoing renovations to Wilson Hall, Delalue wrote that the reconstruction “is an excellent illustration of the work to improve accessibility that the University will continue to undertake in the years ahead.”

Overseeing the implementation of DDIAPs

Within the DIAP, the University required administrative and academic units to create their own departmental diversity and inclusion action plans, or DDIAPs, The Herald previously reported. The report introduces new accountability mechanisms that encourage departments to fulfill goals established in their DDIAPs.

In addition to creating the DIAP Recognition Awards to reward departments that prioritize diversity and inclusion, the OIED will penalize departments in rare instances when “efforts to progress … are stalled or thwarted,” according to the report. Academic and administrative “units that cannot meet the standard of excellence Brown sets as a community will be unable to hire … until expectations are met,” according to the report. These departments would also be unable to recruit new graduate students.

In her email to The Herald, Delalue wrote that while the OIED oversees this process, it reviews individual departments “in consultation with the Provost and, when necessary, relevant Deans.”

Additionally, Delalue wrote that the DDIAPs “should be viewed as ‘living documents’ that can be updated. Both academic and administrative departments are required to submit annual summary updates each year and can reach out to OIED at any time with questions or for support in the process.”

Community Engagement Working Group report

The DIAP also recommended that the University assess its external relationships with the Providence community. The University formed a working group through the Office of Government and Community Relations to “evaluate and report on Brown’s contributions to Providence and Rhode Island,” according to the DIAP.

Over the past year and a half, the Community Engagement Working Group conducted a survey to “inventory and help strengthen and coordinate community-facing programs that currently exist, identify gaps in services and provide information” to maximize the University’s “positive impact” throughout the state, according to the report.

The survey did not ask individuals from Providence to assess services provided by the University. Katie Silberman, associate director of community relations and co-chair of the Community Engagement Working Group, said it “was really (about) … getting a baseline, so it was intended to be internal to the Brown community.”

But the University still receives feedback from community partners through institutions such as the Swearer Center for Public Service, which is “already engaged in a really deep way,” Silberman added.

Using the results from the survey, which included input from 460 on-campus organizations and intitiatives, the working group found that a periodic, voluntary survey assessing the University’s community engagement would be “inherently incomplete” and that community engagement was both “decentralized (and) … not always coordinated with community partners,” according to the report.

“A lot of really great work is going on, but a lot of people don’t know about it,” Silberman said.

The working group’s report recommended the University “expand central resources at Brown to support community engagement throughout the University” by promoting its community engagement work and establishing a “graduate and medical schools coordinator,” according to the report.

Since the majority of University community engagement projects are centered around education, the working group’s report also recommended that the University “develop a strategic approach to education outreach at Brown that coordinates activities across the University.”

ADVERTISEMENT