In a 2016 Washington Post editorial, President Christina Paxson P’19 wrote that we are living in a “time of fierce debate about whether institutions of higher education are becoming places that stifle speech in the interest of protecting students from ideas and perspectives they don’t want to hear.”

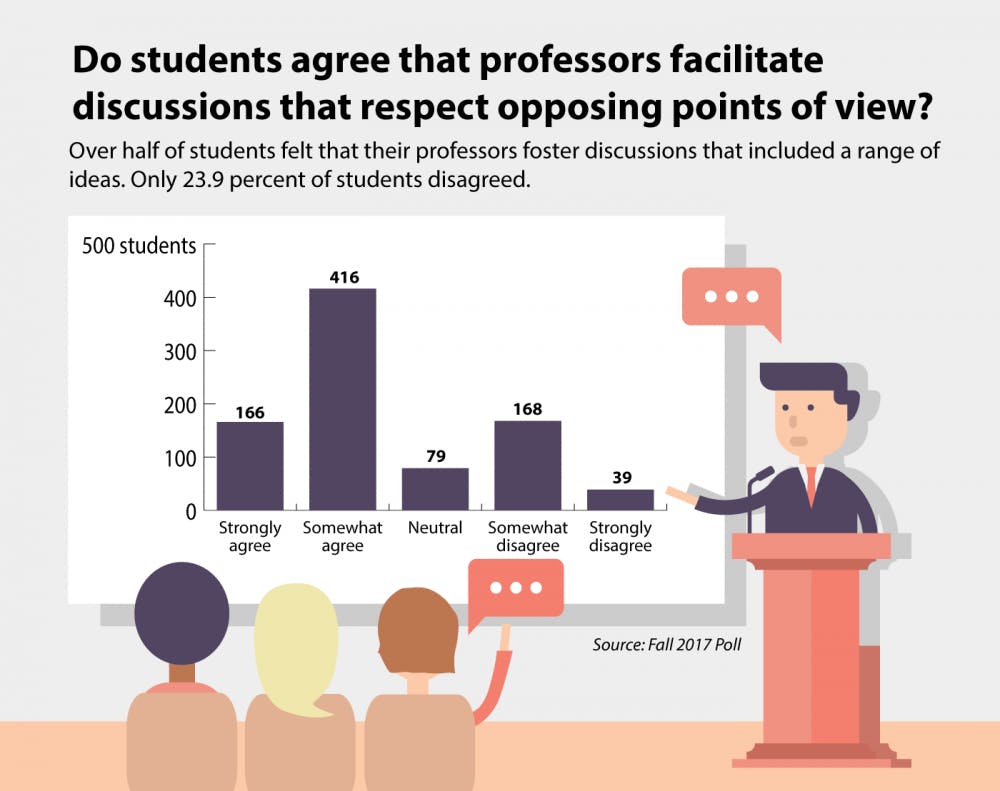

According to The Herald’s fall 2017 undergraduate poll, 67 percent of Brown undergraduates strongly or somewhat agree that professors successfully facilitate discussions that respect opposing points of view, while 23.9 percent of students strongly or somewhat disagree. Nearly three quarters of first-years agree with this sentiment — the highest percentage of any class year.

Patrick Heller, chair of the sociology department, said that at the University, conversations about controversial topics often arise during classroom discussions. “Brown faculty and students have always been committed to openly engaging with all of the difficult and challenging questions of our time,” he said.

Many faculty members in the social sciences and humanities departments have been trained in teaching and leading discussions during their time in PhD programs, said Dean of the Faculty Kevin McLaughlin.

Yet, “if it’s reflected in student or colleague evaluations that (discussions led by a professor) lacked focus or didn’t cover material assigned for class, the department helps (that professor) improve for next year,” McLaughlin said, though he added that the University does not facilitate official trainings.

Faculty can receive individual help from the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning. The center’s website contains a number of links that provide strategies for leading effective group discussions, including advice on creating an inclusive environment, using the method of active listening and asking students to lay out evidence-based arguments. In light of the Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan, the Sheridan Center, along with the Office of the Dean of the College, also ran workshops about how to tackle sensitive topics in the classroom, such as race and gender.

Graduate students also receive instruction on teaching practices. They are allowed to serve as teaching assistants beginning their second year and only after attending a summer workshop or course about effective teaching, McLaughlin added.

Kenneth Wong, chair of the education department, emphasized that good discussions connect with the course’s assigned readings and learning goals. “We want class discussions to be grounded in the knowledge that we cover in a particular session,” he added. To stimulate discussion, Wong usually “pose(s) a couple of critical questions for the class to think through based on the readings.”

When discussing hot topics, such as charter schools in an education policy class, Wong added that professors “have a particularly instrumental role to play, (which is to make) sure that all the voices are heard and articulated.”

Controversial topics can make some students hesitant to share their opinions. “There’s some fear of being politically incorrect … or not saying the right thing, but that can be broken down,” said Anthony Levitas, director of the undergraduate public policy program. “It’s critically important that we don’t shy away from arguments and ideas we don’t agree with.”

Clubs provide additional opportunities for discourse outside of the classroom. The Alexander Hamilton Society hosts U.S. foreign policy debates between professors and outside experts, such as military personnel.

“We try to focus on issues that are highly complex and not easy to answer with a yes or no question, topics that are nuanced, thought-provoking and (ones that) not everyone spends their time thinking about,” said Jake Goodman ’19, president of the Brown chapter. He added that classroom lectures are often one-sided because they are presented from the perspective of the professor.

Not every student agrees that University faculty members give enough space for opposing viewpoints. Charis Edwards ’21 noticed that teaching assistants and professors often hesitate to present ideas with which they disagree.

“Because (they) don’t want to encourage (their) listeners to investigate a perspective (they) think is problematic or incorrect, it promotes ignorance to ignore the existence of other opinions, especially when (professors are) charged with giving an educational overview,” Edwards said.

“In my public health class, we often discuss policy interventions that would probably have wonderful effects on the improvement of public health, but we rarely discuss the fact (that) those same interventions could be viewed as drastic government overreach,” Edwards wrote in a follow-up email to The Herald, adding that this ignores “a very real perspective.”

“We ought to learn how to listen to one another … (and) how to build our knowledge base so that we can continue to mature professionally as well as academically,” Wong said.