For some students, going out to eat can make or break a friendship.

“The first time you say, ‘I can’t go,’ then it becomes five times, then eventually they don’t even call you anymore because they know you’ll say no,” said Aidea Downie ’18, a first-generation student.

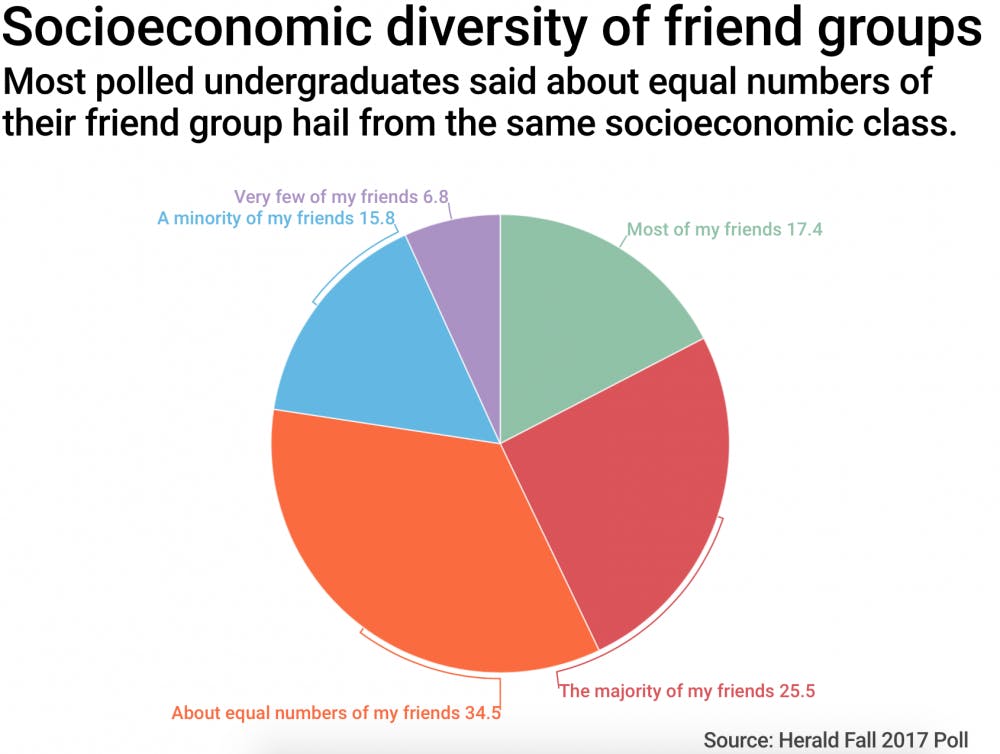

Small actions like these might help explain why many students find themselves friends with people mostly from their socioeconomic background.

Of 854 students polled by The Herald’s fall poll, four in ten said most or a majority of their friends were of the same socioeconomic background as they were. Results varied significantly by respondents’ financial aid status. Of students who receive grants covering all costs, 25 percent said “very few” of their friends were of the same socioeconomic background, whereas only one in 20 students receiving no financial aid reported this.

Responses also varied significantly by the race of respondents, with black and Hispanic students less likely to have a majority of friends from the same socioeconomic background. Black students were the least likely to report that they had most or a majority of friends from their same socioeconomic class, with three in 10 reporting this. Comparatively, about half of Asian students, and four in 10 white and Hispanic students shared this experience. Half of students identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native and 40 percent of Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander students reported having a majority or most friends of the same socioeconomic background, but this was out of a sample of 10 and five respondents, respectively.

“There’s a lot of research in social psychology that shows that people prefer to hang out with people who they perceive as similar to them,” said Gregory Elliot, professor of sociology. “While it has short-term benefits, in that it can be comfortable in the moment, it also has long-term costs — where huge chasms develop between groups and nobody feels like reaching out to the other side.”

The University has taken steps to increase diversity, notably with its Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan launched in January 2016. Though the recently admitted class of 2021 is considered the University’s most diverse class — 40 percent of the class identifies as students of color, 43 percent receive need-based aid and 26 percent have no expected parental contribution — factors like race and socioeconomic background continue to influence friend group disparities on campus.

“I think diversity is harder to achieve than people think it is,” Chaplain of the University Janet Cooper Nelson said. “When people are truly different than we are, it’s not always easy to know them and not easy for them to know us.”

For many first-generation and low-income identifying students, joining a predominantly white and wealthy university can be difficult. More University students come from the top 1 percent than the bottom 60 percent of the income bracket, according to a study reported by the New York Times.

First-generation and low-income students like Downie often feel the need to find people who can understand their experience at the University — having to stay on campus for Spring Break or worrying about paying for textbooks.

“For me, with all these financial challenges, it’s been helpful to have people who understand what I’m going through,” Downie said.

She points to racial and class-based educational segregation as strongly influencing not only who gets to come to Brown, but also who students socialize with when they are here.

Another contributing factor is that students who come from elite circles may carry over those relationships when they arrive on campus, said Michael Shorris ’19.

“The networks people come from are intentionally structured so that people of a certain background hang out only with people from that same background,” Shorris said. “You go to the same beach club, same country club, same program abroad … and namely go to the same schools that are very much exclusionary and then end up at an Ivy League school like Brown.”

Abby Levy-Westhead ’19 said she came to the University with several friends from her private high school in New York City, which formed the basis of her initial friend group.

Although Levy-Westhead said her friend group has since expanded, she acknowledged that socioeconomic background can play a factor in what organizations students choose to be a part of, such as her work for the business team of the Ivy Film Festival.

“Often times, the students most interested in that come from backgrounds where raising money for arts is important. That tends to be more of an upper class background,” Levy-Westhead said. However, she added that other organizations that she is a part of, such as her sorority and Brown Elementary After-school Mentoring, consist of students from more diverse socioeconomic backgrounds.

While developing affinity communities for marginalized groups of students is important, students from more privileged backgrounds should be more conscious about who they become friends with, said Justin Willis ’18.

“It’s important to interrogate who you become friends with and why,” Willis said. “Students might ask: ‘Why is my friend group all white? Why are there no people of color in this friend group?’ At the same time, I don’t think friend groups should play a game of affirmative action.”

Peter Simpson ’20, who is a Minority Peer Counselor from a predominantly Latinx high school of immigrant students in Brooklyn, arrived at the University consciously seeking to develop a diverse friend group. One of his high school teachers advised him to make sure he branched out, he said, and he took the advice to heart.

“She was like, ‘What’s the point of only making a ton of black friends?’” said Simpson, the son of Jamaican immigrants. “Which is just to say that there are multiple places on this campus and life in general where you’ll find great people who don’t have the same skin tone as you. I think she meant, ‘Don’t sell yourself short by thinking that people who don’t have the same skin tone as you can’t offer great friendship.’”

On an institutional level, Associate Dean for First-Year and Sophomore Studies Yolanda Rome said that continuing to invest in identity centers for students, such as the recently launched First-Generation College and Low-Income Student Center, helps foster more integration in student groups.

“The centers are making an effort to bring others into their spaces,” Rome said.

Ally training workshops for groups ranging from the LGBTQ+ community to undocumented students may help other students understand their position of power in relation to the historically marginalized people represented by these centers, she said. The University has recently increased funding for all of its diversity centers, she added.

According to Cooper Nelson, students can be uncertain of how to enter into conversations with others who have differing identities, perhaps fearing potential backlash.

“I think at the moment, friendship, university work, interactions can feel full of landmines to students, as though at any moment something will blow up on them,” Cooper Nelson said. “It’s difficult to get the courage or patience to wade into conversations where the person on other side doesn’t think the way you think.”

To develop a space that allows these conversations to take place, Cooper Nelson encourages embracing diversity not only in the content of ideas professed within the classroom, but also in the pedagogy of how these ideas are taught by creating a classroom where students of all backgrounds feel comfortable engaging in difficult topics like race or class differences.

Stratified friend groups are not necessarily indicative of a lack of interaction between students of different backgrounds on campus, said Assistant Professor of History and Religion Andre Willis. When students socialize, they want to be comfortable where their culture is most easily “translatable,” he added.

For Willis, the strength of Brown’s campus is that it forces students to confront differences while providing them with spaces to relax with those who don’t need to “translate” their identities.

“What’s most important is the kind of nitty gritty, quotidian encounters that come from being in a classroom, being on a team or sharing a bathroom or dining hall,” Willis said. “I think this environment is rich for consistently encountering and negotiating vast differences.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Abby Levy-Westhead ’19 said that students from the organizations she joined tend to be in her socioeconomic background. In fact, Levy-Westhead said she is a part of organizations that consist of students from more diverse socioeconomics backgrounds. The Herald regrets the error.