Last month, a bill that would cap the proportion of registered sex offenders in homeless shelter beds at 10 percent for shelters whose capacity exceeds 50 people passed in the Rhode Island State House. A coalition of activists are now asking via petition that Gov. Gina Raimondo veto the bill, arguing that the legislation is “against the public interest.”

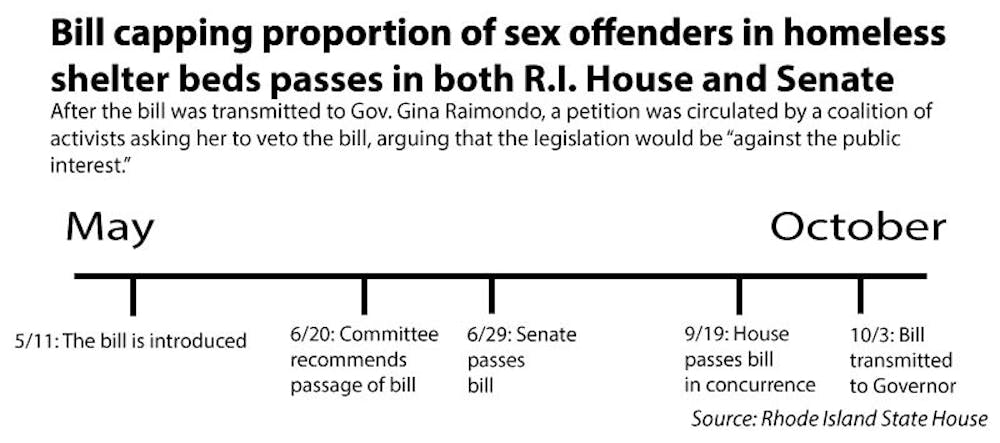

The bill passed the state Senate in June after the Senate Judiciary Committee recommended it for passage. The bill was passed in concurrence by the Rhode Island House of Representatives Sept. 19, and the veto petition was sent to Raimondo Sept. 26.

Seven individuals, including several directors of homeless shelters and non-profits, co-signed the petition to the governor. Forty to 50 individuals will be displaced if the bill is passed, which would create a public safety concern both for the displaced individuals, as well as the larger community, according to the petition. If passed, the bill would take effect Jan. 1, 2018, and the petitioners note that this would leave people homeless in the dead of winter. This would also increase risks of recidivism, petitioners say.

Perceptions of the bill are sharply polarized, and while detractors argue that the legislation jeopardizes public safety, supporters say the bill actually defends it.

State Sen. Frank Lombardi, D-Cranston, is a co-sponsor of the bill and introduced it alongside State Sen. Hanna Gallo, D-Cranston. Cranston is the location of Rhode Island’s largest homeless shelter, Harrington Hall. Harrington has 112 beds which are open to single men. “Harrington Hall has the highest number per capita of registered sex offenders transported there at any given time in the state of Rhode Island,” Lombardi said. This disproportionate concentration of sex offenders in a single neighborhood was the impetus for the bill especially because “the residence hall surrounds at least three elementary schools,” he said.

The question of appropriate maintenance of distance between schools and sex offenders is no new issue in Rhode Island. Convicted sex offenders have been restricted from living closer than 300 feet from any school property since 2008, The Providence Journal reported. In June 2015, the General Assembly expanded this to 1,000 feet for Level III sex offenders — those most likely to re-offend. This law placed 64 percent of Providence off-limits to these registered sex offenders, according to the Journal. In October 2015, the lawsuit Freitas et al. v. Kilmartin was filed challenging the law’s constitutionality as violating due process; after the case was filed, a judge placed a restraining order on the law, effective to this day and as long as the case remains unresolved.

“It’s very sad that we have a significant population of people who are required to register as sex offenders that have no place to live but Harrington Hall,” said Andrew Horwitz, petitioner and assistant dean for experiential education at Roger Williams University. Although the 1,000-foot rule is not in effect, the critics of this bill say that sex offenders do not have options other than Harrington Hall because of policies in other shelters and the 300-foot restriction. “We’ve got such incredible restrictions on where registered sex offenders are allowed to live that pretty much any place in Rhode Island that has affordable housing is off-limits for somebody who is a registered sex offender,” Horwitz added.

Concerning the safety of the public, “what reduces recidivism is stability,” Horwitz said. “When you render somebody homeless” by limiting the number of beds available to them in shelters, “you destabilize them,” he said.

One of the “public safety” concerns in Lombardi’s district is cases of sex offenders being dropped off at the shelter and loitering if no beds were available. He characterized the bill as an “incentive to have all of these homeless shelters share — not overburden Harrington Hall only with registered sex offenders.”

Lombardi had not heard about the petition but was not surprised to learn there was one; “there was a very vibrant debate” in the Senate, he recalled, “given the polarizing issues involved; on one side the issue of public safety and on the other side is the issue of homelessness.” Though he supports the bill, Lombardi recognizes more progress is needed to be made toward finding permanent solutions to homelessness, including for sex offenders. “We need the judiciary, we need law enforcement, we need the public housing folks,” he said.

The petition proposes an alternative path from the bill: a “study commission” that would devote time and resources to considering viable options for housing for registered sex offenders, which could inform future legislation. It also suggests potential amendments to the bill, such as changing the date it would take effect and limiting its applicability to Level III Sex offenders.

Horwitz himself is in favor of building more homeless shelters and having a more decentralized homeless system to relieve Harrington and the neighborhood; but fundamentally he said he views shelters themselves as only rudimentary solutions to homelessness. He would prefer legislation creating more affordable housing and repealing “irrational” housing restrictions to address Harrington’s predicament.

The main plaintiff in Freitas et al. v. Kilmartin, John Freitas, was a Level III sex offender. Barbara Freitas, director of the Rhode Island Homeless Advocacy Project and formerly homeless herself, is his widow. She was another of the seven signatories of the petition.

Freitas echoed Horwitz’s concerns. The bill’s “attempt to keep the public safe is failing miserably, because they will end up in the street,” she said. Freitas explained that sex offenders are at least accounted for in a homeless shelter due to the requirement to register. This means that “public safety” is better served by keeping homeless shelters’ numbers of sex offenders uncapped for community members and visitors alike.

Freitas does not expect Raimondo to heed the petition. Freitas says she was part of a previous attempt to convince Raimondo to veto the 300-foot rule, without success. “Nobody wants to have the veto go through about sex offenders. That’s a sure way to have yourself not get elected,” Freitas said.

If the governor were to veto the bill, there would be no effort by the legislative branch to override the veto, according to Lombardi. The bill was transmitted to the governor Oct. 3. She is required to sign or veto legislation within six days of transmittal. The bill is “currently under consideration for action in the coming days,” according to the governor’s press office.

Correction: Due to an editing error, a previous version of this article stated that the bill was passed in the State Senate in May, In fact, it was passed in the State Senate in June. A previous version also contained an incorrect titled for Andrew Horwitz, petitioner and assistant dean for experiential education at Roger Williams University. The Herald regrets the error.