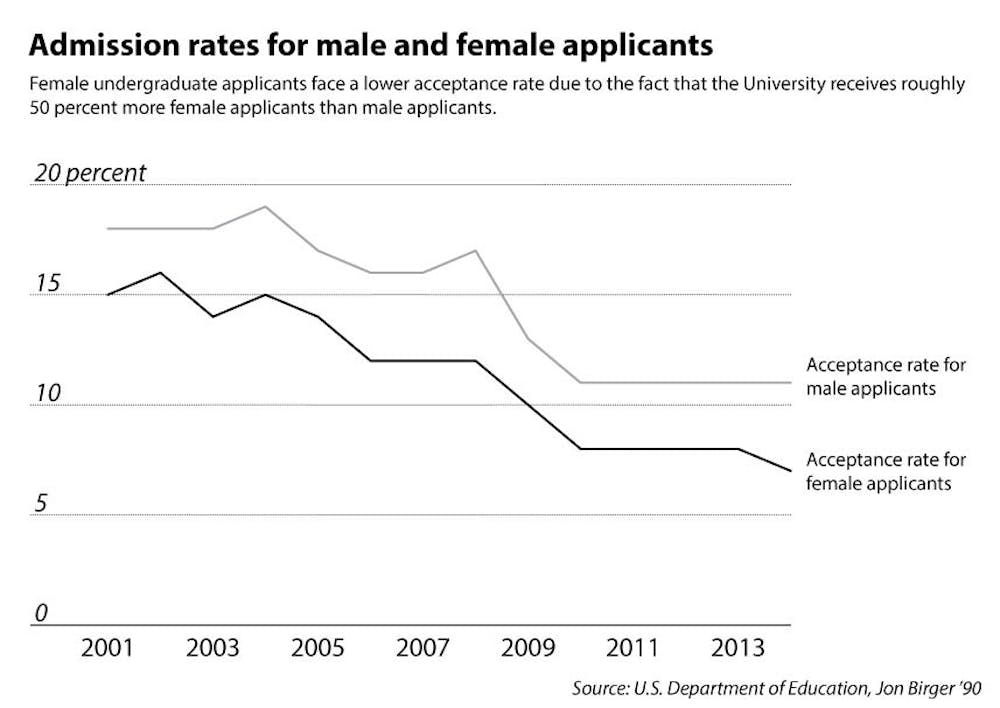

With the early decision admission process underway, one factor may hold more weight than applicants realize: gender. For the past 15 years, the University has accepted male applicants at a rate 3 to 4 percentage points higher than that of female applicants.

While this phenomenon is not specific to Brown, it has caught the eye of one particular alum. In a column in the Washington Post, Jon Birger ’90 claims that many private colleges and universities, including his alma mater, “discriminate against female applicants.”

While Brown’s female applicants are accepted at a lower rate than males, they have still comprised the majority of the undergraduate student body since 1994, when female enrollment first outpaced male enrollment at the undergraduate level.

“It shouldn’t be twice as hard for the women to get in based on their gender,” Birger told The Herald. “They shouldn’t be taking gender into consideration.”

This spring, the University will celebrate 125 years of women on campus, culminating in an alumni conference. “Here is Brown patting itself on the back while, for the last 10 years, they’ve been blatantly discriminating against women,” Birger said.

Gender balance

For the 2014-15 application cycle, the University received roughly 50 percent more female applicants than male. From this lopsided applicant pool, 11 percent of males were admitted versus 8 percent of females, ultimately producing a freshman class with a 54-46 female-male gender ratio for the class of 2019.

“We’re trying to bring in a class of interesting, talented students from diverse backgrounds, but gender balance is critically important to us,” said Logan Powell, dean of admission. “We do strive to have gender balance on campus, so being close to 50-50 would always be our goal. But we’re never going to make a decision on the basis of gender alone.”

Gender balance is a goal in admission offices across the country, particularly at liberal arts colleges. “Today, a lot of the private schools are obsessed with keeping their gender ratio as close to 50-50 as possible,” said Birger, who explores the issue of gender ratios in his book “Date-Onomics: How Dating Became a Lopsided Numbers Game.”

If 50-50 is the goal, then a female-male ratio of 60-40 seems to be the upper limit that colleges are willing to hit.

“If you look at, for the most part, smaller liberal arts colleges, they are in a position where they really do have to make some decisions on the basis of gender. Otherwise, their gender balance would begin to be higher than 60 percent female. And I think for those small liberal arts colleges, that’s the tipping point,” Powell said.

This unspoken upper limit for female enrollment is not a new phenomenon. In 2006, Kenyon College’s Associate Dean of Admissions Jennifer Delahunty Britz wrote a New York Times op-ed that notes the 60 percent tipping point, a threshold that, when passed, elicits “a hint of desperation in the voices of admissions officers,” she wrote.

The fear is that, once an undergraduate student body becomes more than 60 percent female, the school will be less appealing to both male and female applicants.

“Once you become decidedly female in enrollment, fewer males and, as it turns out, fewer females find your campus attractive,” Britz wrote.

But Birger said he doesn’t find this a compelling reason to admit male and female applicants at different rates. “Putting your thumb on the scale and fixing the admissions process to make the social scene more palatable — I don’t think that’s right,” he said.

But Powell maintains that the University has yet to reach this “tipping point,” at which “you really do have to start thinking about some very deliberate actions, either on the recruiting side … or deliberately in the admissions process,” he said.

“We do not do that. We do not recruit men any differently than we do women. We don’t admit men any differently than we do women.”

How it’s legal

Had both male and female applicants to the Brown University class of 2019 been admitted at the average rate of 9.5 percent, the admitted students would have been 60 percent female, broaching the “tipping point” territory.

Instead, the University admitted female applicants more selectively to yield a freshman class with a gender ratio closer to 50-50.

Private colleges and universities like Brown are able to consider gender as a factor for admission due to a so-called “loophole” in Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972.

“The original Title IX, as people began to think about introducing it, was ‘no sex discrimination in any school that gets federal funds,’” said Bernice Sandler, a women’s rights activist and key figure in the creation of Title IX.

But lobbyists from private colleges and universities — particularly those in the Ivy League — opposed certain facets of the law and fought to maintain their ability to consider gender when admitting undergraduate students. Adding an exemption for private institutions seemed like the only way to get Title IX passed, so the modification was made to the legislation, Sander said.

“When Title IX was being passed, this was the most important change in the law,” Sandler said. “Originally, it was no discrimination,” but “we couldn’t get anybody to support it.”

When Title IX became law in 1972, it dictated that “private schools are allowed to discriminate on the basis of sex” in admission, a change to the legislation that Sandler said she “tried to fight.”

Today, private colleges and universities use this loophole to maintain gender balance in their undergraduate populations despite the dearth of male applicants.

Sandler still laments the loophole. “It’s there, and I’m still unhappy about it because it does mean that some of the men (who) are accepted aren’t as smart as some of the women they turn away,” she said, speaking to the national issue at private colleges and universities across the country.

Where are the boys?

In addition to considering gender the admission process, some schools are investing in efforts that they hope will attract more male applicants.

Just this month, the Wall Street Journal reported that in the last 10 years, 86 colleges and universities have added football programs to their campuses to address the gender disparity, and 67 of these schools saw an immediate increase in male enrollment.

Other schools may be enhancing certain academic programs in hopes of attracting more male applicants.

In recent years, the University has invested $88 million in a new engineering building, slated to be completed in early 2018.

“The fact that they’re investing in a program that has more men than women is not a coincidence,” Birger said.

In the spring of 2016, 65 percent of engineering degrees granted by the University went to male graduates. Additionally, 66 percent of the degrees that the University granted in physical science went to male graduates. And for the class of 2020, there were 16 percent more male applicants interested in physical sciences than female applicants, Powell said.

The University’s acceptance of males and females at different rates stems from “a real attempt to try to recruit, admit and enroll more students, male or female, interested in the physical sciences,” and “it just happens to be the case that there are more young men interested in the physical sciences than there are young women interested in the physical sciences,” Powell added.

“In my perfect world, (the School of Engineering) is equally compelling to young men and young women,” Powell said. But, he added, “the fact that we have an engineering program — and many liberal arts colleges do not — is a big driving force behind who is interested in Brown by gender.”

Powell said there is “nothing deliberate on our part” to reach the 3 to 4 percentage point difference in male and female admission rates, but rather that this statistic is actually “a reflection of our attempt to strengthen particular academic programs,” he said.

As the University aims to bolster its presence in the physical sciences, male applicants are inadvertently favored in the admission process, Powell said.

“As an alum,” Birger said, he is “skeptical” of this argument.

“No matter what the motivation is, it’s clear that they are favoring male applicants,” Birger said. “Which is more important to you, having fair, sex-blind admissions, or filling every seat in a particular department?”