While all applicants to the University’s undergraduate program can expect regular decisions to be released online March 31, the University’s 51 departments with doctoral programs review and select applications in varied ways behind the scenes.

For fall 2016 admission, the Graduate School received a total of 6,136 applications for doctoral programs. If the past two admission cycles are any indication, about 12 percent of the applicants will be accepted, according to data sent to The Herald by Peter Weber, dean of the Grad School.

Central administration

At the crux of the graduate admission process, the Grad School takes on a very administrative role, Weber said.

The Grad School helps departments recruit and interact with prospective students, specifies “admissions policies … with standardized test scores” and provides a vendor for all graduate applications — CollegeNET.

The administration also sets the budget for each department, which is formulated by “many, many conversations with the department,” Weber said. The budget takes into account “each department’s needs, the number of students, the number of courses (and) the number of faculty in the department,” he added.

Some departments may find themselves vying for funds more than others.

“Many programs in the humanities at Brown would like graduate stipends and summer support funds to be more competitive with those of our peer institutions,” wrote Janine Sawada, professor of religious studies and East Asian studies and director of graduate studies for the department of religious studies, in a follow-up email to The Herald.

After departmental budgets are set, departments can then decide how to structure their application review processes and set the number of students they will admit — referred to as the “target number,” Weber said.

Finding a fit

Across various doctoral programs, most faculty members emphasized that fit was an important factor for admission. Ross Cheit, professor of political science and international and public affairs and DGS for the department of political science, summarized the criterion of “fit” with a question: “Are there people here who you want to work with and who would want to work with you?”

There needs to be a faculty member in the department “who can actually advise the dissertation,” said Evelyn Lincoln, professor of history of art and architecture and DGS of the department.

The Doctoral Program in Behavioral and Social Sciences makes sure each candidate could work with a specific faculty member mentor based on compatibility of research interests, said Kate Carey, professor of behavioral and social sciences and DGS of the department.

Unlike the undergraduate admission process, “We really are saying: Which professors did they say they wanted to work with? Which professors have expressed that they are interested in working with them?” Cheit said.

Most departmental graduate studies directors said they expect students to contact professors with questions regarding the fit of the department around the application deadline. “People who are thinking of applying very often get in touch in the fall,” Sawada said.

“We encourage (applicants) to talk with professors. We encourage them to visit. Most of (the faculty members) will make time to have a conversation with a potential applicant,” Cheit said.

In accordance with faculty members’ prioritization of fit, some doctoral students sought out the University for specific professors and research areas.

Aimee Bourassa GS, a graduate student in the department of political science, said she contacted Assistant Professor of Political Science Rebecca Weitz-Shapiro before applying to the University to make sure her “research interest would be a good fit.”

“I was specifically interested in working with (Professor of History of Art and Architecure and Department Chair) Sheila Bonde because she was studying a particular area that I was interested in pursuing,” said Laura Chilson GS, a graduate student in the department of the History of Art and Architecture. She only applied to Brown and would have continued her professional career in marketing if she had not been admitted, she added.

Along with fit, departments heavily weigh an applicant’s academic record, which consists of transcripts and Graduate Record Examination scores.

Applicants need to have “the general ability to do the work that they want to do,” Lincoln said.

Those accepted to the Doctoral Program in Political Science tend to have both compatible research interests with a given professor and a strong academic record, Cheit said.

The departments also consider letters of recommendation and personal statements. “We are looking for evidence that the applicants work well with others and show initiative … that they are intellectually alive,” Carey said. “We are going to be working closely with them for four to five years and then hopefully have an ongoing relationship with them for years to come,” she added.

Some data-based departments also emphasized research potential as an influential factor for admission. “The most important component” for graduate admission is research potential, said Oded Galor, professor of economics and DGS for the department. “The department can gauge research potential by reviewing letters of recommendation, personal statements and research papers,” he added.

The Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences prioritizes applicants with master’s degrees because those students “have had more time to get research experience and potentially get presentations or publications,” Carey said. “Not everyone needs to have a lot of (research) opportunities … but if a person has (them), it bodes well for success at a department like ours, which is research-focused,” she added.

Making decisions

The departments all have different application review processes. The Department of Economics receives the largest number of applications — about 800 — and divides the applications by quality before the “more promising applicants are read by many” faculty members, Galor said. The department admits 30 to 40 students to yield a class of about 15.

In contrast, some smaller departments may have a single person read all of the applications, Weber said.

After reading through the applications, some departments may have a recruitment day for a short list of finalists.

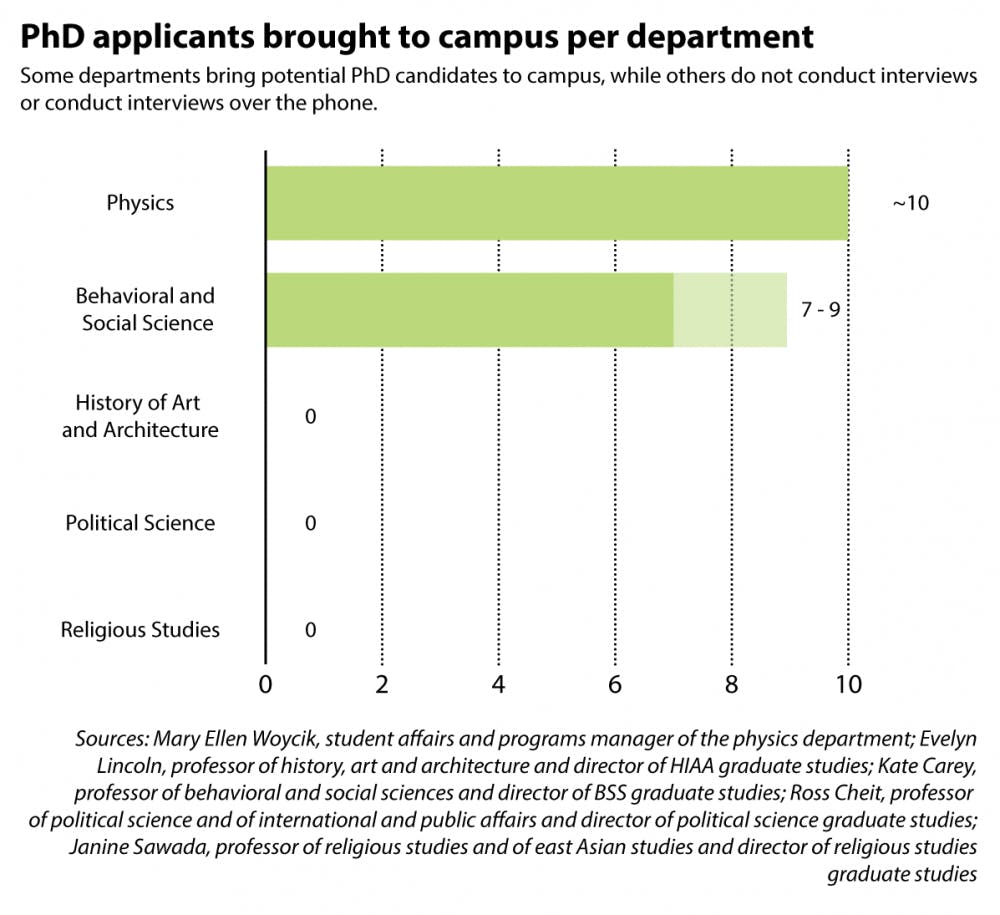

The Department of Behavioral and Social Sciences invites seven to nine finalists to tour facilities, talk to current students and meet one-on-one with professors, Carey said. “Clearly there is information you can glean from an applicant when you meet face to face rather than reading a highly edited, written document,” she added.

The Department of Physics invites its accepted students — usually around 10 — to visit campus in the spring. “Our reimbursement policy is to cover … two nights of hotel accommodations, meals and up to $500 of reasonable travel expenses,” wrote Mary Ellen Woycik, student affairs and programs manager of the department, in an email to The Herald.

Aislinn Rowan GS, a doctoral student in pathobiology, traveled to Brown for an interview and extolled the benefits of an in-person interview. “Certainly, the one-on-one interviews could be conducted over Skype, but then you don’t get to see the facilities, the labs, the campus or anything like that, and you don’t get to meet any of the current or other prospective students,” she wrote in an email to The Herald.

Some departments do not have the funds to fly out finalists for the graduate spots. “We do not require interviews because we cannot pay for the student to come here, (though) when we make a finalist list … we will often call the student to get the information that we need to make an informed decision,” Lincoln said of the history of art and architecture interview process.

After the departments individually review the applicants, Weber reviews all the final decisions, and his staff mails out letters of acceptance to admitted applicants.