Depending on whom you ask, Brown may be the nation’s sexiest, smartest college. It might also be the best, smartest party school. It may even rank in the top ten U.S. colleges.

But each ranking stacks the various factors differently and has its own idea of which should be taken into consideration, and the diversity of these ranking systems can produce remarkably different results.

This fact can actually be “empowering for students” because they are presented with more information to compare and contrast universities, said Steven Goodman, educational consultant and admission strategist at Top Colleges. For international students, these rankings can be especially important. They may not be indicative of “the experience you will have” at a university, but they serve as an indication of how much a degree is “worth after graduation,” said Kyoka Kosugi ’18 of China. “I looked specifically at top 20 U.S. college rankings and top 20 colleges for International Relations because I want to work outside of the U.S. and it helps to have a degree from a university that is more well-known or ranked highly.”

On the contrary, the variety of rankings can also lead to students become rankings-obsessed and misuse this information, especially when they believe they “have to go to a school that is ranked in the top 20,” he added.

Schools like Brown can receive dramatically different evaluations depending on each system’s methodology — while the University ranked 14th this year in U.S. News and World Report’s National Universities Ranking, it was 8th in Forbes’ America’s Top Colleges list.

University-college

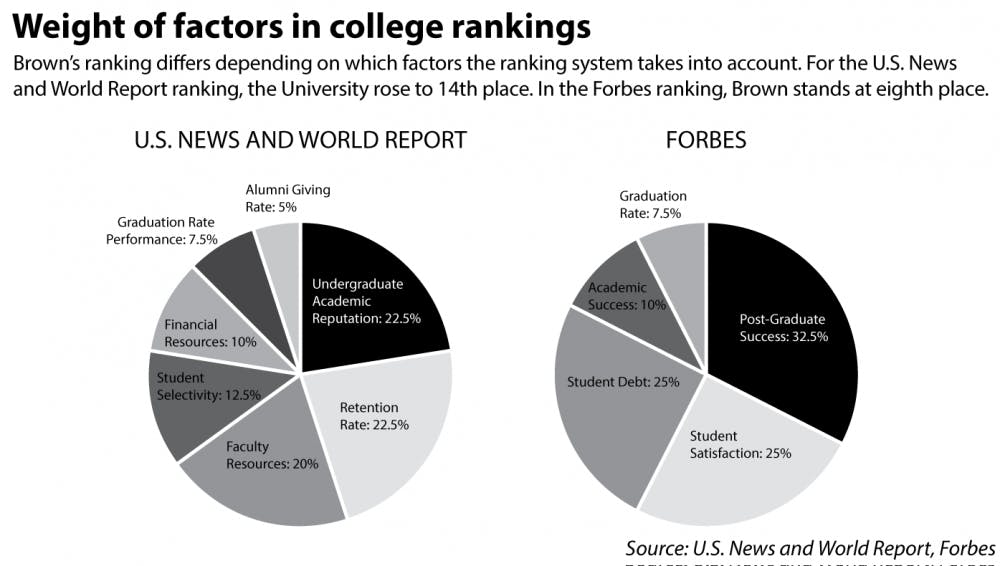

The U.S. News’ ranking is one of the most well-regarded rankings in the country, with a fairly diverse set of factors represented in its methodology. Its overall rankings take into account seven different factors: undergraduate academic reputation (22.5 percent), retention rate (22.5 percent), faculty resources (20 percent), student selectivity (12.5 percent), financial resources (10 percent), graduation rate performance (7.5 percent) and alumni giving rate (5 percent).

While Brown’s spot at 14 marks an improvement from last year’s 16 — a result administrators attributed to a miscalculation of selectivity — the result still lands Brown at seventh place in the Ivy League. Cornell is tied at 15 with Vanderbilt University and Washington University in St. Louis.

On undergraduate academics reputation — a factor calculated from peer assessments by other universities and rating by high school counselors — Brown continues to perform strongly. This year, in ratings completed by high school counselors, Brown received a 4.8 out of five, and in the U.S. News’ Best Undergraduate Teaching ranking, Brown placed third, falling behind only Princeton and Dartmouth.

Brown’s relative strength in this area affirms the University’s continued identity as a “university-college” — a term coined by former President Henry Wriston to describe a research university that prioritizes undergraduate education. The importance of this term to both faculty and students manifested itself in 2013 when President Christina Paxson’s P’19 10-year strategic plan — “Building on Distinction” — initially left out the term, while conveying intent to expand the University’s graduate division. Due to faculty and students’ dismay, Paxson included the term in a later draft. Breaking down rankings and faculty passion illustrates that Brown’s undergraduate teaching is best known to its peers.

Money over matter

Over the years, Brown has consistently done well on Forbes’ America’s Top Colleges ranking, which calculates returns on investment by focusing on student satisfaction (25 percent), post-graduate success (32.5 percent), student debt (25 percent), academic success (10 percent) and graduation rate (7.5 percent).

“The Forbes list of 650 schools distinguishes itself from competitors by our belief in ‘output’ over ‘input,’” wrote Forbes Senior Editor Caroline Howard in an article detailing Forbes’ methodology. “Our sights are set directly on ROI (returns on investment): What are students getting out of college?”

Brown ranks eighth on Forbes’ America’s Top Colleges 2015 list, placing fourth in the Ivy League behind Princeton, Yale and Harvard.

But a look at President Barack Obama’s new College Scorecard seems to reveal a darker picture of post-graduate success. Released Sept. 12, the “College Scorecard” shows that Brown graduates who received federal financial aid have the lowest median salary 10 years after entering the school than students at the other Ivies. Though well above the national average of $34,343, Brown students’ median salary of $59,700 falls well behind that of peers like Harvard ($87,200), Columbia ($72,900) and Dartmouth ($67,100).

Brown also has the third highest average annual cost in the Ivy League. At $25,005 after aid considerations, the cost for students receiving federal financial aid is only lower than Cornell’s and Dartmouth’s.

Behind the pack

In contrast, Brown’s relatively low position in global ranking websites such as Times Higher Education can be accounted for by the University’s smaller research focus compared to that of other Ivy Leagues. Brown ranked 54th in the “World University Rankings 2014-2015,” coming in seventh place in the Ivy League, higher only than Dartmouth, which ranked 152nd. Cornell, the 6th in the Ivies, placed 19th.

For the THE ranking, reputation for research excellence among peers, research income and research productivity are taken into consideration when determining a university’s research score, which then comprises 30 percent of the overall score. Scoring 54.2, Brown performed noticeably worse than all Ivies sans Dartmouth.

THE’s methodology “does tend to favor large research-intensive universities. … It’s based mainly on how much your research is shared and disseminated and how much you’re contributing to new knowledge,” said Phil Baty, editor-at-large of THE. “So, if you’re a teaching-focused university, it is going to be tougher for you in this ranking.”

But THE’s rankings are scaled so that small institutions can compete fairly with the large research-focused universities, Baty said. “You can almost argue less research can sometimes be better for universities because they can make sure they are publishing just at the very high end, the very best work, and not spreading themselves too thinly,” he said. “There is a new ranking coming out on Sept. 30, and I think it’s good news for Brown,” Baty added.

Rankings on their mind

Universities might not have a great deal of control over how they are assessed, but they care about the rankings “like teenagers care about their looks,” Goodman said.

“The rankings directly affect the undecided potential applicants from the following year,” Goodman said. For students who are conflicted about which university to choose, they have a wide variety of rankings to help them make a decision, he said.

With rankings in mind, universities may try to manipulate statistics to gain an edge over their peers. For example, a university might supply more money to students to improve its “financial resources” score on U.S. News — the type of practice Obama argued in 2013 rewards colleges for raising costs.

Having a large portion of the rankings based on factors independent of the university such as “reputational surveys and analysis of research publications” can help prevent these potential manipulations of statistics, Baty said.