“We need to bring the sex back into birth control,” said Larry Swiader, senior director of digital media at Bedsider, an online educational resource on birth control operated by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. “Sex is better and healthier when you have the peace of mind about the birth control you’re using.”

Swiader criticized the predominantly scientific approach to birth control marketing in the past few years as counter to what women find most relatable when choosing an optimal contraceptive. The intrauterine device, or IUD, in particular has come into focus recently as a method in need of better promotion. In February, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics released a data brief concerning the use of long acting reversible contraceptives, such as the IUD and implant. The study found a five-fold increase in the use of these methods among women ages 15 to 44 over the last decade, with IUD use increasing 83 percent from 2006-2010 to 2011-2013. Swiader said there has also been a notable increase in visitation to the IUD and implant pages on the Bedsider website. “I’m able to report that the IUD and the implant are visited more now than when we launched the site” in November 2011, he said.

A June 2014 Time magazine article praised the IUD, deeming it the best method of birth control on the market for sexually active women. The IUD is a small T-shaped rod inserted into the uterus by a trained healthcare provider. Once inserted, the IUD creates a hostile environment for sperm, making it hard to fertilize an egg.

The IUD is more effective than birth control pills — one out of 100 women will get pregnant each year while using the IUD, while six to 12 out of 100 women will get pregnant while using the pill, according to the CDC. The greater effectiveness of the IUD stems partly from the fact that “there is no need to remember to do something daily or before intercourse. … And no need to buy refills each month,” wrote Melissa Nothnagle, associate professor of family medicine and a director of the women’s reproductive health concentration at the Alpert Medical School, in an email to The Herald.

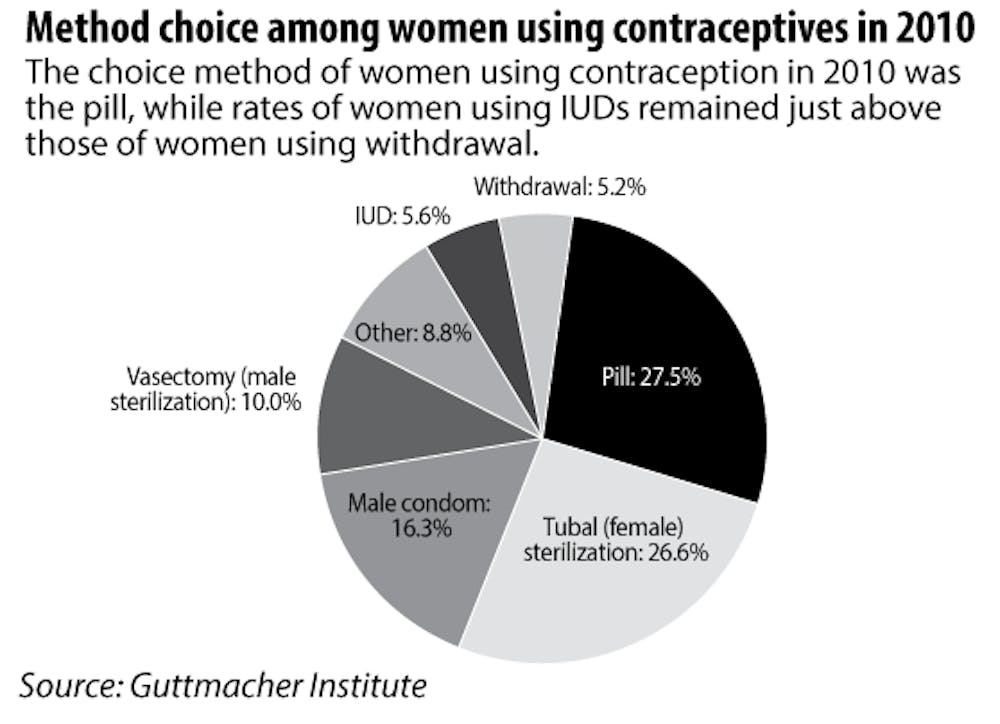

Though highly effective and requiring minimal attention, the IUD remains uncommon compared to other forms of contraception, such as the birth control pill and condoms, with 6.4 percent of American women ages 15 to 44 using an IUD between 2011 and 2013.

The Sexual Health Education and Empowerment Council hosted a workshop Monday evening entitled, “Plan A, B or C: Do You Have an Option? (Access to Contraceptives),” as a part of its Sex Week programming. Student feedback from the workshop revealed that women on campus believe their birth control options at Brown are limited.

Students at the workshop discussed the challenges they face when accessing sexual health resources and appraising reproductive health options. Many attendees said they were aware Health Services and BWell Health Promotion provided condoms and emergency contraception but not any other methods of birth control. In fact, students can obtain birth control pills, dental dams, the Ortho Evra patch, the Depo-Provera shot, the NuvaRing and spermidical foams and jellies at Health Services.These resource and knowledge barriers may explain why the IUD also remains uncommon among women at Brown.

Attempts at access

The students in attendance drafted a list of recommendations for BWell Health Promotion and Health Services to increase access to sexual health resources at Brown. The list highlights students’ desires to have more agency in choosing contraceptives. One barrier to this choice is that Health Services will not insert an IUD, though it will refer women to local providers.

Ardra Hren ’15 said her attempt to obtain an IUD was a “huge ordeal.” Hren conducted her own research and visited a Planned Parenthood in Providence to have it inserted, she said.

“I was meaning to do it for awhile before I actually did it,” Hren said, adding that she could see how the inability to receive the IUD on campus “would be a deterrent” for women at Brown.

Jeffrey Peipert ’82 P’11, professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a former professor at the Alpert Medical School, said he conducted surveys about contraceptive use at Brown as part of a consistent study that began in the 1970s. He also conducted another survey in 2011. Very few sexually active women who responded to the survey indicated that they used an IUD. Peipert said he was surprised by how few women at Brown were choosing the LARC methods and gathered that the lack of access on campus may be a hindrance.

Peipert stressed that once women face an access barrier, they are less likely to pursue a particular contraceptive. “I’m putting IUDs in high school students, so why wouldn’t we see more of it at Brown?” he asked.

Peipert is also an author of a study entitled the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, which enrolled nearly 10,000 women, removed the financial costs of LARCs and provided counseling on all birth control methods. With financial barriers removed and education available, the study found that two-thirds of all women chose a LARC.

Fighting the stigma

A rocky history has also played a role in women’s hesitance to choose the IUD. Physicians and educators have been working to alter long-held perceptions.

Though the IUD has been on the market for decades, many women have been reluctant to use them due to widespread complications in the 1970s and 1980s.

The IUD’s public image was tarnished by a plethora of problems with the first product, the Dalkon Shield. Though the shield’s popularity grew quickly — sales hit 2.8 million by the early 1970s, according to the CDC — the shield was connected to high rates of pelvic inflammatory disease, which can be extremely painful and risk infertility. Due to the flaws of the shield, IUD usage faced a sharp decline in the 1980s and rates remained low until 2002.

Though the design of the IUDs on the market has since changed and the IUD has been touted by physicians as one of the most effective forms of birth control, the stigma associated with the method persists.

Most of the women interviewed for this story spotlighted a difference between their parents’ perspectives and their own, noting that their parents remain wary of the IUD.

“When I talked about it with my mom, she was supportive of my decision to go off the pill but a little apprehensive when I told her about my decision to get an IUD,” said Isabella, a junior who requested to be identified by only her first name due to confidentiality concerns.

Isabella said her mother’s generation was “most notably affected (by complications with IUDs), so we spent a lot of time looking into what had changed since then.”

Lizzie Davis ’15 also said her mother expressed disapproval of her getting an IUD. “My mom thought I wouldn’t be able to have kids or get pelvic inflammatory disease,” she said.

Traditional beliefs of the dangers associated with IUD use, particularly for younger women, are not unique to the patients. The stigma persists among many within the medical community. Davis said her doctor at home also did not support giving her an IUD, since she had not yet had children. In order to get her IUD inserted, Davis sought a doctor in Providence who “could relate to me more and had a much more current view,” she said.

An unwillingness among doctors to propose the IUD as an option results in part from the “medicolegal climate” in the United States and the device’s troubled past, Nothnagle wrote.

“Physicians have been reluctant to recommend IUDs to any woman who has not already had children, fearing that any subsequent fertility problems would be attributed to the device,” she wrote. “Many providers still follow outdated limits on eligibility for IUDs, which has probably been the biggest barrier to U.S. women accessing IUDs.”

Swiader said Bedsider has focused on provider outreach especially. He said those at Bedsider understand how important providers are “to the equation of people getting their birth control right.”

Peipert also stressed the ease of inserting the IUD as long as a provider is trained. “If they draw blood, they can put in an implant. They just have to be trained … It’s not rocket science,” he added.

Preference for the pill

Many women opt for the pill as a more accessible and accepted method, though most of the women interviewed said they switched to the IUD because of complications with the pill.

“I had been on the pill for close to five years, and I had flare-ups of some of the side effects,” Isabella said. “Various doctors tried to alleviate them by changing my dosage, but it was still wreaking havoc on my body.”

Davis has also been on birth control and said she “felt that had a lot of negative side effects for me, and I wanted to try something else … I felt that I was very moody and irritable, and I didn’t want to be taking that dosage of hormones on a day-to-day basis.”

Julia, whose name has been changed to maintain her confidentiality, said the pill caused more than hormonal changes. For some pill users, “it can thin the lining of your vulva, and it can cause really bad tearing during sex,” she added.

“It also decreases your natural levels of lubrication, so I was having really painful sex,” Julia said, adding that she felt better as soon as she went off the pill and has since chosen Skyla — the smallest of the IUDs and one that offers a lower dose of hormones than Mirena, another variety on the market.

Unforeseen costs

As Peipert’s Contraceptive CHOICE project discovered, the cost of the IUD, which can be as much as $1,000, can prevent many women from selecting the method.

Since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, all methods of contraception should be covered without any out-of-pocket expenses for patients. Furthermore, federally funded Title X clinics and Planned Parenthood provide the full range of contraceptive options to low-income and uninsured women on a sliding-scale basis.

Peipert said he enrolled several members in the study whose employers, such as religious organizations, were exempt from providing contraception in their health plans.

Julia named various unexpected costs as a downside to opting for the IUD.

“It was fully covered by my health insurance, so the actual cost of the device was zero dollars,” Julia said, though she added that her health insurance did not cover the actual cost of visiting the doctor. “So that was an unexpected cost, plus having to go so far away. I had to rent a car to get there.”

Nevertheless, Julia believes the IUD is ultimately cost-effective. “You stop getting your period as long as it’s a hormonal replacement IUD, so you save money on tampons.”

“You save money on condoms if you’re with a partner that you trust and you’ve both been tested,” she added.

Side effects and successes

In spite of multiple barriers, women are more likely to opt for an IUD than they have in past years. According to Nothnagle, the IUD is the most popular form of reversible contraception among women physicians.

Women physicians “appreciate the convenience and recognize that the method is extremely safe and effective,” Nothnagle wrote. “Busy students probably share some of these same values.”

When asked about their overall experience with the IUD, all of the women interviewed said it has been a positive one. While the insertion of the IUD is painful for many women, “All side effects are not created equal,” Swiader said. “We shouldn’t downplay that there’s definitely some discomfort with it,” he said, adding that “women who are really well-prepared for that manage the temporary side effects associated with insertion very well.”

“I feel proud of myself,” Davis said. “I feel excited that I found a good option for myself.”

-With additional reporting by Camilla Brandfield-Harvey