Administrators plan on conducting a survey from the Association of American Universities to measure campus attitudes toward sexual assault this April, despite criticism from researchers studying sexual assault over the survey’s perceived ethical violations.

The University paid $87,500 to the AAU, a nonprofit organization comprising 62 public and private research institutions including Brown, for use of the survey, said President Christina Paxson P’19.

Though Title IX does not require institutions to implement surveys assessing sexual assault on campus, the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault recommended that universities do so.

Of the 62 institutions that are members of the AAU, 27 schools including the University — along with non-member Dartmouth — have signed a contract to participate in the survey, according to a Jan. 22 AAU press release. More than 800,000 undergraduate, graduate and professional students will be offered the survey, making it the largest research initiative to gather data on sexual assault to date, according to the press release.

As sexual assault continues to be a hot button issue on college campuses across the country, the University’s participation in the review surfaces several concerns over the survey’s transparency, implementation and potential effects on students.

Writing wrongs

The AAU’s invitation to universities to participate in the survey triggered much controversy, with sexual assault researchers sending four different letters to university presidents and five psychology professors releasing a statement in protest.

Sixteen experts on sexual assault sent a Nov. 17 letter to the presidents of the universities that are members of the AAU, as well as 15 university presidents in the Consortium on Financing Higher Education, which was also invited to take the survey. The letter urged these presidents not to sign a contract with the AAU for a survey they had not yet seen.

A follow-up letter was sent Nov. 22 and signed by 16 new researchers in addition to the original 16. Forty-five scientists signed a third Nov. 25 letter, and 56 scientists signed a fourth letter Dec. 3 critiquing survey’s perceived condensed timeline and lack of transparency.

A version of the survey reached five active or emeritus professors of psychology Jan. 13: Sarah L. Cook of Georgia State University, Louise Fitzgerald of the University of Illinois, Jennifer Freyd of the University of Oregon, Mary Koss of the University of Arizona and Jacquelyn White of the University of North Carolina. The researchers sent a detailed report Jan. 27 listing their concerns about the survey to participating university presidents and institutional review boards.

AAU spokesman Barry Toiv said he did not know how the researchers got a copy of the survey. “Westat has sent drafts to the participating universities — to the folks working on the survey— to get their views and to initiate the internal review board process,” he said.

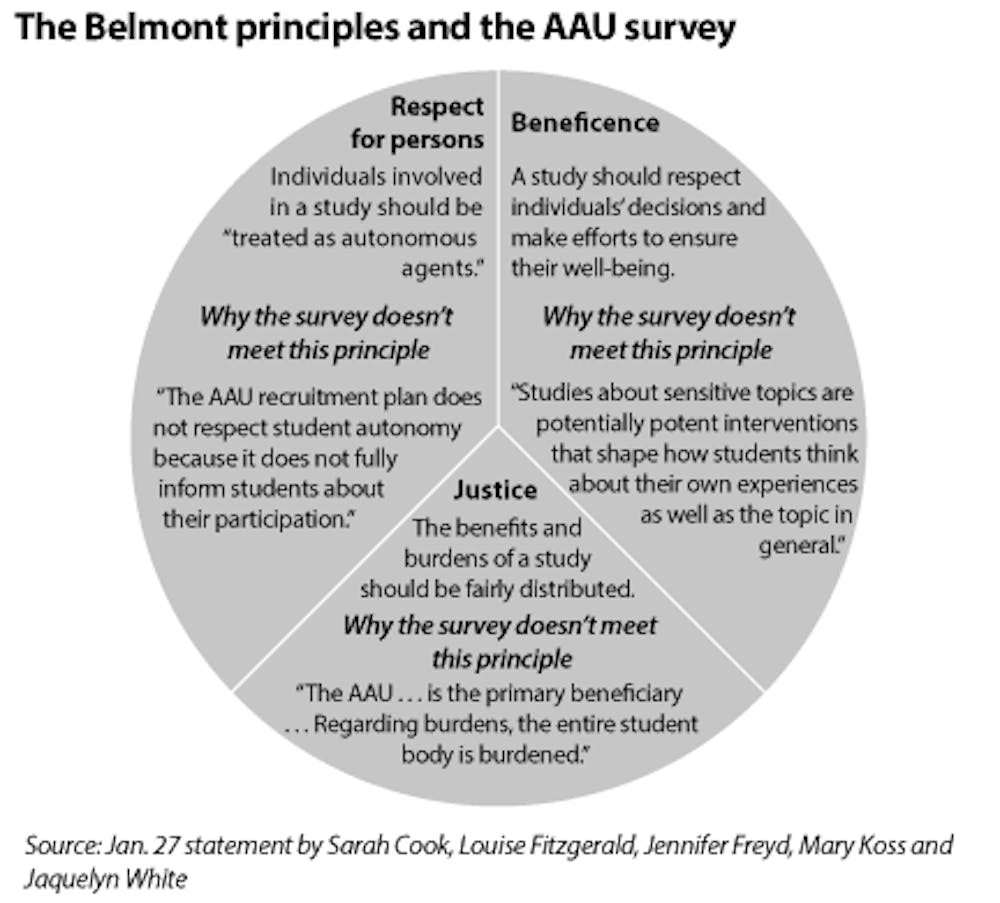

The researchers argued that the survey goes against three principles of the Belmont Report, a set of tenets created in 1978 to protect human subjects in research. The first principle, a respect for persons, is violated because the AAU misleads its subjects about the value of their responses in the survey, the statement read.

Researchers also argued that the survey breaks the second Belmont principle requiring researchers to protect students from harm. The survey’s language, they contended, limits definitions of sexual assault and sexual harassment, inadequately addressing survivors’ experiences of sexual violence.

The third Belmont principle, which aims to protect justice in research, addresses which groups reap the survey’s benefits. The researchers argued that it is the AAU, rather than the institutions, that will benefit from the data.

The five researchers have since passed the case to Bill Flack, associate professor of psychology at Bucknell University and co-founder of Faculty Against Rape, a group “dedicated to getting more faculty involved in sexual assault issues on campus,” according to its website. Flack intends to share the materials with reporters to publicize the case, he said.

Outside and inside

Rather than create the survey independently, the AAU partnered with research firm Westat, according to a Nov. 14 AAU press release.

Russell Carey ’91 MA’06, executive vice president for planning and policy, chaired the AAU’s Request for Proposals team, which was responsible for choosing Westat, he said.

Westat “had the capacity and the relevant expertise, having done on small and large scales survey research around sexual violence,” Carey said, adding that Westat brought in several experts from both inside and outside the company who knew the best practices for conducting scientifically rigorous surveys.

“It’s everything from understanding how to work with colleges and universities … to the technical expertise to host” the online survey without crashing when large volumes of users access the site, Carey said.

Sandra Martin, professor of maternal and child health at University of North Carolina and an expert in violence prevention and women’s health, chairs a team of professors who will work with the AAU and Westat to design and administer the survey, according to the Nov. 14 press release.

Two Brown researchers will join Martin’s team of survey designers: Melissa Clark, director of the Center for Population Health and Clinical Epidemiology, and Lindsay Orchowski, assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Carey said. The presence of two University professors on the team “reflects the leadership role Brown has played in initiating this survey,” he said.

The survey is based on one designed by Victoria Banyard ’88, professor of psychology at the University of New Hampshire, Carey said. Banyard’s survey was included in the report issued by the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault.

Dollars and census

With its $87,500 price tag, the survey may represent a significant financial undertaking for participating universities. Flack called the “tens of thousands of dollars” required for participation a major concern.

“I do this kind of survey on my own campus,” Flack said, noting that while Bucknell is small, it still costs him only $500 to annually complete such a survey.

The AAU publicly released a Frequently Asked Questions document Nov. 20 that included a cost breakdown of the $87,500 price. $68,000 went directly to Westat to work with universities to promote and launch the survey, obtain student data and analyze and publish university-specific results.

Of the $68,000, $15,000 will provide “material incentives” for student participation, Toiv said. The rest of the funds will go toward the development of the survey, according to the document.

Among the researchers’ other worries is that the survey will take a census approach, in which every student on participating campuses will be asked to complete the survey. A stratified random sample will be pulled from all of the completed surveys, and only this data will be used in research analysis.

Some of the participating institutions, such as Ohio State University and Texas A & M University, have student populations upwards of 50,000.

“You don’t need to sample anything like that to do a survey like this,” said Freyd, one of the five researchers who drafted the statement, adding that only a stratified random sample of 300 to 2,000 students needs to be surveyed to gather accurate data. “What worries me is that this will be using a lot of students’ time, and it’s not clear for what purpose,” she said.

“One of the things people think is, ‘How bad can a survey be? Isn’t more data always a good thing?’” Freyd added.

The five researchers worry that the long survey will exhaust students, who may stop filling out questions or not give questions their due attention, Freyd said.

“It’s important in cases of sexual violence that the research doesn’t harm students,” Freyd said. “Surveys can do more harm than good.”

“There is a concern with survey fatigue,” Paxson said. “We wouldn’t conduct another campus climate survey right away.”

“Brown felt very strongly that all students should be asked” to take the survey, Carey said. “It was very important in terms of our sense of community that everyone’s voice matters. The reason for the randomized sample embedded in the survey is to make sure it’s as rigorous and as representative as possible.”

Posts for participation

The AAU survey plan urges institutions to encourage students to complete the survey by sending 10 tweets and 10 Facebook posts, according to the Jan. 27 statement.

“We are unaware of any scientific survey engaging in such a high level of reminders, which to some will impose unnecessary burdens and may well seem like harassment,” the five professors wrote in their statement in noting that the process would violate the third Belmont principle of ensuring justice in research.

Paxson said it is common to ask students to take surveys through various tactics.

The wording of the social media posts also preoccupied the five professors.

“When people use terms like sexual assault, it may not be a term that some students who have experienced sexual violence even identify with,” Freyd said. “People can get very focused on the idea we’re talking about crime by using legal definitions of crime. The damage done by sexual harassment and gender discrimination is more fundamentally understood as a civil rights violation.”

Peer pressure

Though the survey will be reviewed by several Institutional Research Boards, it will not be peer reviewed, leading some to speculate as to its commitment to rigorous scientific methodology.

“If we’re going to get good data about the prevalence of sexual assault on different campuses, as the White House Task Force has asked to be done, it ought to be done in a public manner, in an open scientific process, and it ought to involve active communication with experts in the field,” Flack said.

While Westat’s own “independent federally recognized Institutional Research Board” approved a draft of the survey and will ensure the final survey follows ethical standards, universities are allowed to share the survey with their own IRBs for approval, wrote AAU president Hunter Rawlings in a Feb. 3 letter in response to the researchers’ statement.

Brown’s IRB will also review the survey, Paxson said.

IRBs exist to ensure that research is ethically conducted, but they do not take the place of peer review, Freyd said. “The people who sit on IRBs are not experts in any specific research domain.”

Freyd said she expressed doubt at the validity of the approval of the survey draft. “They approved a survey that wasn’t finished,” she said. “I’ve never heard of my (university’s) IRB approving a draft.”

Public or private?

Questions have also emerged about the manner in which the survey results will be distributed.

“Our primary concern was the secretiveness of it,” Freyd said. “Science highly values transparency and an opportunity to critique each other’s work. Of all topics, you don’t want to be secretive about sexual assault. Sexual assault thrives in secrecy.”

Flack said he is concerned that the AAU keeps the survey information so private and releases only the “most general information.”

The AAU plans on publicly releasing the survey results once they are fully developed, according to a Dec. 1 letter. Additionally, the AAU has encouraged participating universities to announce their results, Toiv said.

Paxson said she intends to announce Brown’s data, as the Task Force on Sexual Assault’s interim report recommended.

“If you look at the Sexual Assault Task Force’s work at Brown so far, they’ve made it very clear that they’re taking an approach that is trauma-informed and that is data-informed. That’s vitally important,” Paxson said.

“It’s very important that we’re transparent with our results,” she added. “In fact, one of the big benefits of being part of a survey that’s administered to multiple campuses is that people will have the opportunity to compare the results across institutions.”

But Flack demanded why the survey was not made public before the universities had signed the contract, adding that, “There’s no reason that transparency can’t be the way to go from the get-go.”

One size fits most

The survey may take a unique form at each of the 28 participating institutions, with its language changing to reflect different campus characteristics.

The survey will feature the same questions for all institutions, except for five questions whose wording will include the names for university-specific offices, programs or resources, according to the press release. Institutions will also have the opportunity to add a link at the end of the survey directing students to another survey with school-specific questions, Rawlings wrote in the Dec. 1 letter.

Brown will take advantage of this chance to add its own “fairly narrow” questions, Carey said. But the survey’s short timeline — the release date is set for April — will not allow the University due time to construct an extended list of appropriate Brown-specific questions, he added.

“I think of this survey really as a baseline —it will be something we want to repeat over time,” Paxson said. “It will give us a way of assessing whether what we’re doing is effective, otherwise we won’t know.”

The Task Force on Sexual Assault’s interim report requires that a survey be administered on a regular basis to Brown students. “We’ll learn a lot in this first process and learn what’s going to be best going forward,” Carey said. He added that he expects the survey to operate on an annual or biannual basis, but that he wouldn’t “want to go much longer than that.”