The flow of federal research funding to the University is only now starting to recover from the 2013 federal sequestration. As a result of the sequester, the total pool of research funds at the University decreased by 13.7 percent between 2013 and 2014, said Vice President for Research David Savitz, but funding for new research proposals in the first half of fiscal year 2015 is up significantly — about 30 percent — from 2014.

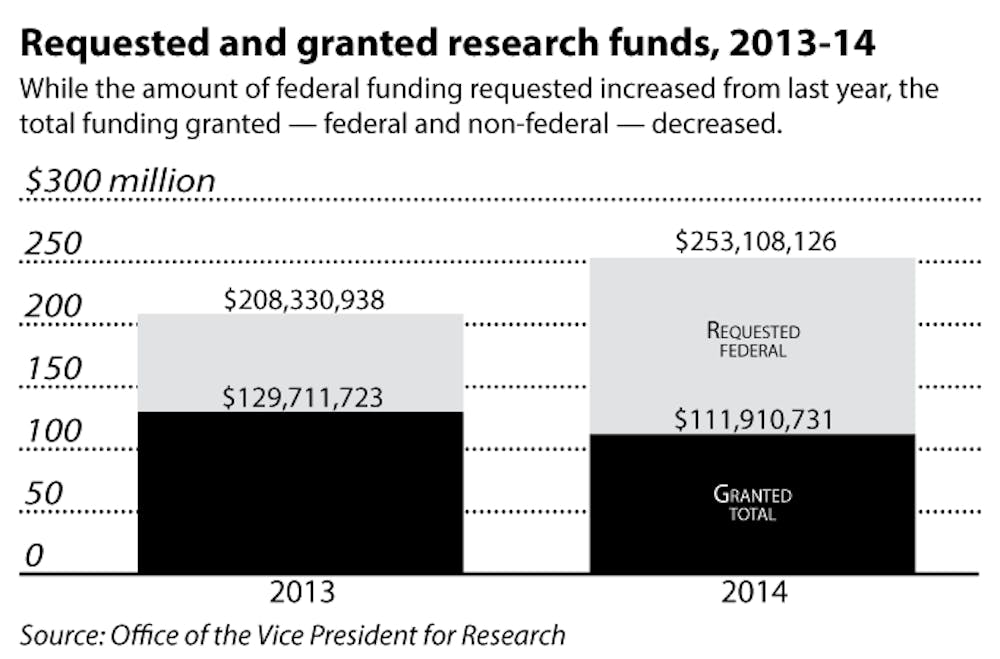

Total research funds amounted to $129,711,723 in 2013 and $111,910,731 in 2014, Savitz said. During those two years, federal funding accounted for roughly three-quarters of total research

The sequester, which began March 1, 2013, led to deep budget cuts, a temporary suspension of funding and delays in new awards, Savitz said. Research funding has not increased since its last peak in 2011, he added.

“More proposals are being submitted for the same pot of money,” so the proportion of successful proposals has declined, he added.

Many peer institutions saw their non-federal funding increase as federal funding declined. For example, at Harvard, when federal funds decreased by 5 percent in fiscal year 2014, the university obtained more non-federal funds to keep total expenditures relatively constant, the Crimson reported Jan. 22.

But unlike at peer institutions, Brown did not make up for the loss of federal funding with non-federal funds: “While the federal sources were declining, there was not a compensation in other areas,” Savitz said.

“Some other institutions were a little bit quicker to recognize the reality that to keep up you have to write more proposals, send more proposals, send them to a wider range of funding agencies and be more resourceful in tough times,” Savitz said, adding that Brown was delayed in responding to the challenges of decreased federal funding.

“It’s all reflecting the activity of the faculty and the success they’re having,” he said, adding that without this extra effort, federal and non-federal funding tend to rise and fall with one another.

“The frustration level is very high among researchers at Brown and across the nation,” said Anne Hart, professor of neuroscience. “Getting funding for research has always been competitive, but great science was always funded before. Now the grant review system seems like a lottery, not a thoughtful proposal review and selection process,” she added.

Faculty members conducting research are also forced to spend more time than usual writing proposals rather than actually engaging in their research, Hart said.

“The faculty have come to realize that funding is remaining tight. The federal budget for research isn’t going to suddenly expand,” Savitz said. The only response is to write more proposals and be more entrepreneurial in order to receive greater funding, he added.

The number of research proposals rose between fiscal years 2013 and 2014 and the amount of requested funds grew from $208,330,938 in 2013 to $253,108,126 in 2014, Savitz said. There was about a $1 million gap between requested and awarded funds.

The more proposals that are submitted, the more likely the University is to receive additional funding, Savitz said.

Though the number of research grants requested began to rise in 2013, new awards didn’t rise until 2014 and money spent on research has only begun to increase in 2015, Savitz said. “There is a lag between each of these events,” he added.

ADVERTISEMENT