Much of the public perception of the 1960s civil rights movement is skewed and needs to be readdressed, said Charles Cobb, a civil rights scholar and visiting associate professor of Africana studies, during a book talk Tuesday.

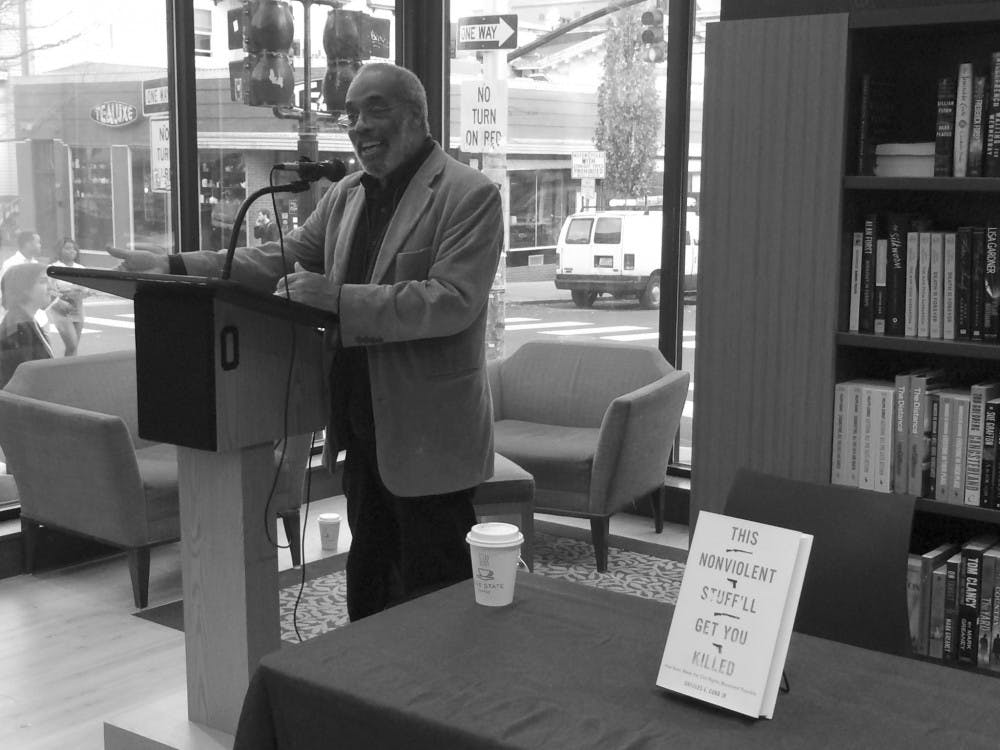

Providence community members and students gathered to hear Cobb discuss his book, “This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed,” at the Brown Bookstore. Cobb previously worked as a reporter for National Public Radio and National Geographic and is an inductee in the National Association of Black Journalists’ Hall of Fame.

“News is shaped more by what is left out than any bias,” he said. “Much of the same thing is true in history.”

While Cobb argued that both scholars and the public distort and misrepresent history in general, he focused on the oversimplification of the mid-20th century civil rights movement in the South. He wrote his recently released book due to his “dissatisfaction with the way the history of the movement is presented,” he added.

Cobb highlighted popular misconceptions of the civil rights movement by sharing an anecdotal conversation that he had with an acquaintance. Cobb said that after he told his friend about his book idea, his friend said, “What the public understands is that Rosa (Parks) sat down and Martin (Luther King Jr.) stood up, and then the white folks saw the light.”

Cobb criticized how Americans study and portray history. “This country is very bad with history,” he said. “It’s as much a cultural problem as it is a political problem.”

While marches led by high-profile leaders such as King were important, history often forgets about the role ordinary black citizens played in the civil rights movement, Cobb said. “If you really want to understand the movement, you have to look at it from the bottom-up.”

Cobb discussed the “organizing tradition” of blacks throughout the American South’s history. As slaves, blacks didn’t participate in protests or sit-ins, but they still organized escapes, revolts and assassinations. This tradition carried into the civil rights movement, which many regular people — including sharecroppers, small farmers and maids — shaped, he said.

Cobb highlighted how harsh the South was toward black people, labeling it a “murderous society” that advertised lynchings of black World War I veterans in newspapers. He also discussed his own arrest when he was working as a young field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Mississippi.

The author said he uses guns as a device for framing the narrative of racial conflict in the South.

Americans need to understand the actions of black people as ordinary humans faced with white terrorism, Cobb said. In this situation, people “will act to protect themselves as best they can,” he said, adding that they may resort to gun violence. Black people in the 1960s saw no contradiction in saying they were part of the nonviolent movement while being simultaneously dependent on armed self-defense for survival.

“I reject the notion that there’s some kind of dichotomy between nonviolence and armed self-defense,” Cobb said, noting instances of gun violence during the civil rights era which he said had furthered the movement but are often forgotten. For example, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, one of the cities in which King organized protests, desegregated in less than a year thanks in part to a group of armed activists who protected peaceful protestors from being harmed. “They kept down violence in this Ku Klux Klan town,” Cobb said.

Ku Klux Klan members didn’t pursue violence against people they knew would fight back, Cobb noted. “As much as white supremacists talked about white supremacy and ‘necessitated’ white supremacy, they simply weren’t prepared to die for it,” he added.

Cobb stressed history’s continuous impact on society. Problems that blacks fought to resolve in the 1960s had their roots in the founding of the country, he said. Even though laws changed and slaves were freed, attitudes toward blacks prevailed, he added.

This tradition of ingrained racial attitudes tied to Cobb’s argument that the idea of “white people didn’t exist before the United States created them to justify slavery.” A belief in white superiority was necessary to perpetuate slavery as a system, he said.

Cobb also connected the nature of history to the relevance of the civil rights movement today.

“To understand the civil rights movement, you have to understand how ordinary people can effect change. That’s important,” Cobb said. “You don’t want people thinking that they have to be Martin Luther King to change things.”

The author stressed that it is “important for students to see what students can do” to advance social justice, citing the role played by SNCC and students during the 1960s. Campus talks about history and activism are a great way to influence and inspire young people, he said.

Cobb’s future research will analyze what from the 1960s movement is still relevant, he said. “Today, we see things we thought were settled 50 years ago resurfacing, like voting rights,” he said. “It may be time to think about renewing the struggle.”

ADVERTISEMENT