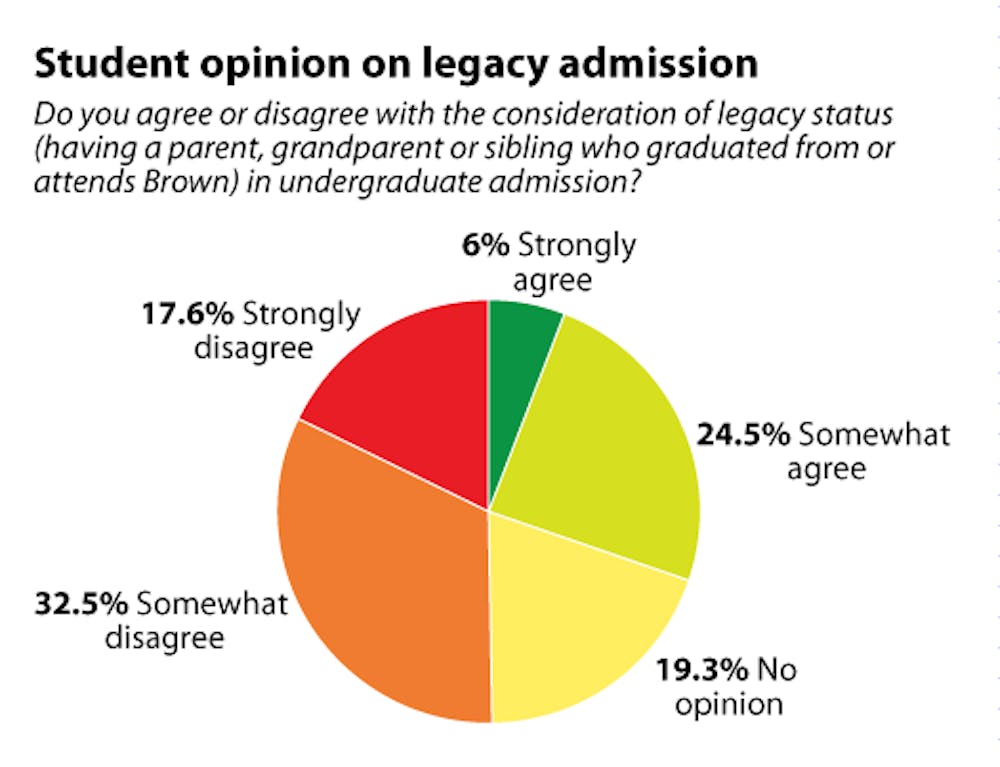

Just over half of undergraduates disagree with the consideration of legacy status in the University’s admission decisions, according to the results of a Herald poll conducted March 3–4. About 30 percent of students agree with the use of legacy status — having a parent, grandparent or sibling who attended Brown — in admission, and 19 percent have no opinion.

Legacy students and varsity athletes were more likely to support legacy status’ use in admission, while those receiving financial aid from the University were less likely to do so.

Nearly half of legacy students agreed with the admission practice, with about 14 percent strongly agreeing, 34 percent somewhat agreeing, 20 percent somewhat disagreeing, 11 percent strongly disagreeing and 22 percent expressing no opinion. About 44 percent of varsity athletes — 14 percentage points higher than the general student body — agreed with the use of legacy status. Students who do not receive financial aid from the University are more likely to support legacy status use than are those who receive any combination of grants and loans.

Though Brown’s admission officers consider legacy status when making decisions, the Office of Admission does not track the acceptance rate for any subgroup of students, said Dean of Admission Jim Miller ’73.

Legacy students usually make up “between 10 and 12 percent of the incoming class,” and admitted students with legacy status tend to enroll at higher rates than the rest of the admitted pool, Miller said.

Having a parent who attended Brown comes into play when applicants “are essentially equivalent,” in which case admission officers “will tilt toward the candidate whose parents attended the college,” Miller said. Admission officers give “small” consideration to grandparent legacy status and “almost no” weight to sibling legacy cases, he added.

But the University does not admit unqualified students on the basis of legacy status or any other criteria, Miller said. “We will never bring a student here we do not think will be successful,” he said.

Many students said they agree that consideration of legacy status is acceptable only if applicants are qualified for admission on the basis of merit.

“It definitely shouldn’t play a large role in admissions … but I don’t think it’s a huge problem,” said Mary O’Connor ’16. The college admission process can “seem a little randomized” so it is difficult to tell why any individual was accepted, she added.

Emily Reif ’16 said considering legacy status on its own would be unfair, but many legacy applicants possess strong qualifications and merit admission. Some students may think their peers with family members who attended Brown do not deserve admission spots, but this can be an unfair perception, she said.

Samantha Wong ’17, a first-generation college student, said she does not have a problem with the use of legacy status and there is value to having students with legacy in a class.

Taking legacy status into consideration is a long-standing admission practice, Miller said.

“The rationale is that Brown as an institution depends on the kindness of others,” he said. Considering legacy status helps build a sense of community in which alums are willing to donate time and resources to the University, he added.

Some universities use legacy consideration in hopes of growing their endowments through increasing alum donations, both of which factor into major college ranking systems like the one developed by U.S. News and World Report, said Michele Hernandez, a college consultant and former assistant director of admission at Dartmouth.

But no research or evidence supports the premise that alum parents are more likely to give to a college if their children also attend, said Richard Kahlenberg, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation who focuses on education issues.

The use of legacy status is likely to continue at Brown. Though the Admission Office frequently reviews its policies, there are no immediate plans to stop considering legacy status, Miller said.

But concerns about improving fairness in college admission practices continue to shape the debate over legacy applications.

As affirmative action admission practices increasingly come under judicial review, legacy practices could also face pressure, Kahlenberg said.

Education experts have varying opinions on the use of legacy in admission and the impacts of the practice.

Stephen Trachtenberg, president emeritus and professor of public service at George Washington University, said legacy consideration can be useful for building community and continuing alum giving but should be used “with discretion.”

“We have an institution that has been built over hundreds of years … through the labor and love of students, alumni and parents,” he said. “This needs to be taken into consideration but in an appropriate amount.”

But to some, legacy status privileges applicants who already have a socioeconomic leg up.

“Legacy acceptance is very difficult to justify,” Kahlenberg said. “It tends to advantage a group of students who are already quite advantaged by the fact that their parents attended one of the best universities in the country.”

Hernandez called the use of legacy in admissions “unfair,” but both she and Trachtenberg said the policy’s detractors exaggerate its impact.

Many different subcategories of students receive special preferences, Hernandez noted. Recruited athletes, for example, are more likely to receive a big “tip” in the admission process than are students with legacy status, who often have stronger academic credentials than those without legacy status, she said.

“It’s not a big bump,” she added. “I think if people understood that, they wouldn’t care as much.”

ADVERTISEMENT