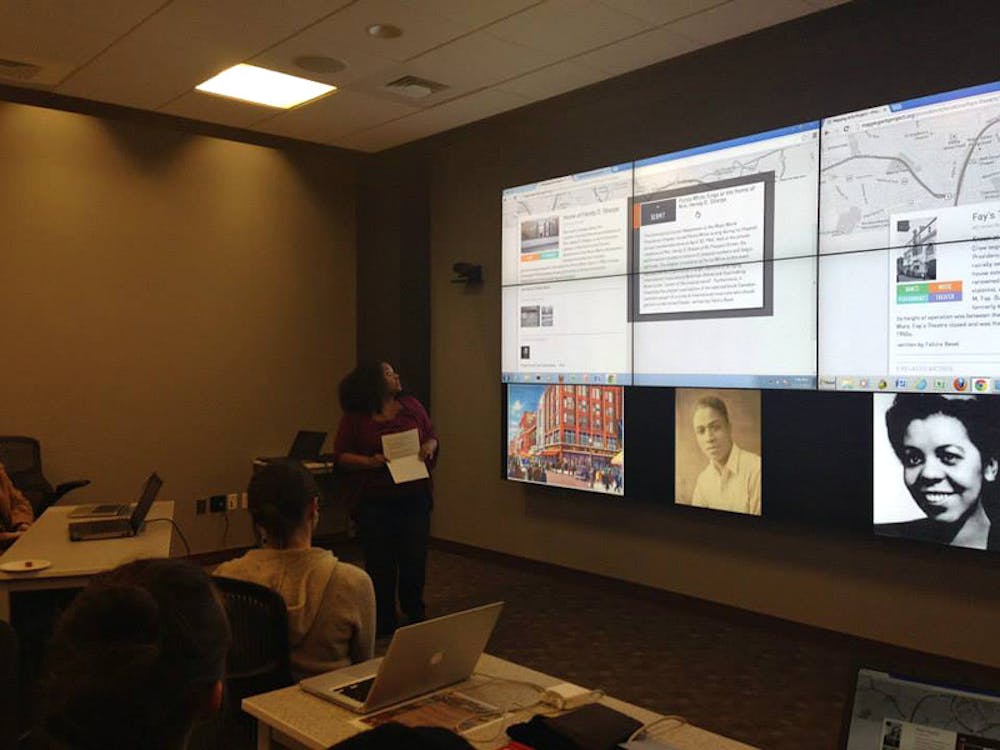

The Mapping Arts Project recently launched a digital map of Providence that marks locations relevant to African diasporic art history from the 1860s to the 1960s. The project was developed by Lara Stein Pardo, an artist, cultural anthropologist and postdoctoral research associate in the John Nicholas Brown Center for Public Humanities and Cultural Heritage, and organized by the nonprofit Blackbird Arts and Research, a nonprofit organization founded and directed by Stein Pardo

“The inspiration behind the project is to connect real places to histories that might seem kind of detached from reality (and) make them more real by connecting them to places we can visit now,” Stein Pardo said, adding she was inspired to start the project while doing ethnographic fieldwork in Miami.

“I came across a book of letters by Zora Neale Hurston … and I started to realize that a lot of them were written in Miami,” she said. “I started to think there must be more sites like this and that would be interesting to call attention to.” Stein Pardo first conceived of the Mapping Arts Project in 2008, though at the time she imagined it would be a much smaller conceptual art piece. She decided to expand the project “because it seemed so necessary.”

“I started the project in Miami, looking for places where artists had lived and worked and then started to develop this map,” Stein Pardo said. “And then I realized — after talking to more and more people about the project — that this was something that was necessary and viable in other cities.” When she arrived at Brown to do postdoctoral work, Stein Pardo decided to integrate the growth of the Mapping Arts Project into the course she taught last semester — AMST 1903H: “Space and Place: Geographies of the Black Atlantic.”

The three graduate students enrolled in Stein Pardo’s course conducted the majority of the research. Providence was selected as the project’s next city only after the course was underway.

Felicia Bevel GS, a first-year American Studies graduate student who worked as a research assistant on the project, said choosing Providence offered the class and the teacher an opportunity to learn more about the city.

Why Providence?

“We were relatively new to the area,” Bevel said. “So it was an opportunity for us to learn more about Providence and its history.”

“I feel like I’ve fallen in love with the city of Providence,” said Keila Davis GS, a second-year graduate student in the public humanities program who took the “Space and Place” class and now acts as the project manager for the Mapping Arts Project - Providence. She said she chose to continue working on the Mapping Arts Project team after the initial class ended, because it aligns with her academic interests. “I’m always fascinated by making history accessible to people,” she added.

Mapping Arts Project - Providence maps black artistic production from the 1860s to the 1960s, while the Miami version covers cultural art from the 1920s to 1950s. Stein Pardo said the time periods were chosen, because they have been somewhat overlooked and represent “the hidden histories of cities.” The period between the 1920s and 1950s in Miami was “between the founding of the city and the arrival of many more people from Cuba and Haiti,” she said. “That was a critical period of time that had been sort of masked in Miami’s history.”

In Providence, the team focused on a larger swath of time in order to represent the city’s historic reputation.

“If you ask anybody about black artistic production in Providence, they’ll mostly point to the theater activity in the 1960s … and then the Civil Rights movement,” Stein Pardo said. “But Providence really prides itself on being a ‘creative capital’ and also a historic city, so I think in terms of black representation, it was necessary to trace a larger trajectory.”

Archives mark the spot

Students used primarily University materials when conducting research for the project, especially historically African-American newspapers.

“My time period was roughly 1930 to 1950,” Bevel said. “Most of my information came from Brown University material that was digitized.”

“The fun part of research is prying and figuring things out,” Davis said. “It was very gratifying to find hidden gems.”

Davis expressed surprise at “how much information wasn’t easily available online,” adding that print resources were still a critical tool.

“Working with the students in Providence was really spectacular,” Stein Pardo said. The graduate students “really connected with people who live in Providence and that has been a really important part of the project.”

Bevel and Davis also applauded community organizations for their collaboration with the project.

“Although a lot of information that we found was pretty accessible through the library system here,” Bevel said, “It was difficult nonetheless to find evidence — especially during certain time periods — of black artists coming through Providence.” She said sometimes this information would be incomplete, underscoring the importance of contacting community members who could fill in the gaps.

The group partnered with the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, said Davis, who is helping the society to plan a larger event for this spring.

Artists of note

Davis said she was surprised to find so much information about black artists connected with the Rhode Island School of Design.

“I didn’t realize how many African-American artists went to RISD (in the early 1900s) so I thought that was really fascinating,” she said.

Another significant historical site is Providence’s Celebrity Club, “the first integrated club in New England,” Stein Pardo said. The son of the Celebrity Club’s founder still lives in Providence and attended the project’s December launch, Bevel said.

For the project, Davis researched Rudolph Fisher ’19, a student commencement speaker for his class who was friends with Langston Hughes and involved with the Harlem Renaissance. “Because he died so young, his legacy didn’t really live on,” Davis said. “He was an excellent writer as well as a successful medical doctor.”

Bevel said the team took on the goal of showcasing African diasporic artists, rather than solely African-American artists.

“We did find several artists that were not U.S.-based,” she said, citing Portia White, an Afro-Canadian singer who performed at Rochambeau House, which holds Brown’s departments of French and Hispanic studies, when it was just a private residence in 1945. Bevel said the team also found several U.S.-based artists who traveled internationally, emphasizing the diasporic theme of the project.

Crowdsourcing

Though the Providence map was officially launched in December, Stein Pardo thinks of the project as continually in progress. The Mapping Arts Project website allows visitors to continuously submit additional material.

The project’s public response has been primarily positive. “I love making sure that people who aren’t in academia can access any research that I do,” Davis said.

“One of the places on the map is the Pond Street Church, and I found out that a class at Brown actually did an oral history about that church,” she said. “So it’s great that people who have done other research can chime in.”

“Some people simply wanted to know more about certain locations that they had no idea had any connection to black artistic production in Providence,” she said, adding scholars often suggested ways to expand the project or develop connections between the artists.

“I would hope that (Brown) students look at (the map) and try to engage with Providence as a city,” Stein Pardo said

Uncharted territory

Bevel is hoping to continue her involvement with the Mapping Arts Project. Though students worked on the project as part of their coursework, they wanted it to be an ongoing endeavor, Bevel said.

The project has been “a collaboration with community members, archivists, artists and other people who really want to see this project expanded and keep it moving forward,” Stein Pardo said.

“We would love to do an event around one of the places on the map,” Davis said. “It would really be a community and Brown event, not just a Brown event.”

Looking ahead, the team also hopes to upgrade the Mapping Arts Project’s social media presence. “We have to keep in mind the changing nature of digital technology,” Stein Pardo said, because technology and aesthetics constantly change.

The team may also “keep adding more and more cities” to the project, though a new location is not yet confirmed, she said.

With the Mapping Arts Project poised to potentially expand its scope and presence,“it has become something that lives beyond the classroom,” Bevel said.

ADVERTISEMENT