Tim, Tom and Craig hurtled down the mountain, three pinwheels of red and blue on an infinite expanse of white, far from Providence. Ice axes desperately striking the mountain, they dragged themselves to a stop after 300 meters, stranded from their trail.

Professor of Geological Sciences Tim Mutch, Tom Binet ’78 and Craig Heimark ’76 had set out together, the first of their seven-man party to approach the summit of Mount Nun, a 7,135-meter peak. Bound by rope, they fell together, too.

The cliffs are slanted at a hostile 60 degrees, and the air seared at 30 degrees below zero. They knew they couldn’t return that night. So they chiseled a ledge in the side of the ice and rested, 22,000 feet above the ground.

The men talked. “Why the hell did we do that? What the hell were we climbing?” Heimark remembered asking himself.

They spoke of their kids and families. Of their love of exploration, of testing the limits of what they could do. Of how hard it was for people to understand why they were doing this.

What they were doing was returning to the Himalayas for the second time in two years, an expedition that would claim Mutch’s life. Why, though, was a question not as easily answered.

A singular attraction

Tall and lanky with wire-rimmed glasses and a shock of sandy hair, Mutch nurtured a boyish curiosity that belied his near 50 years, remembered Rebecca Moore ’77, a member of the first expedition.

In the 1970s, when the University’s New Curriculum was still new, Mutch offered a Modes of Thought course: “Exploration.” The Modes of Thought program sought to inspire first-years’ intellectual curiosity. The course tracked the “singular, compelling attraction” exploration held for men throughout history, according to Mutch’s course description. It culminated with the opportunity to test exploration itself.

The open expedition marked Mutch’s first time leading a Brown group of climbers and attracted a diverse array of students and faculty, most of whom had never taken Mutch’s course. “There was no thread of connection except they all decided to do this very Brunonian thing,” said Liz Wheeler ’79, a member of the first expedition and a Brown professor of psychiatry and human behavior. Students took the initiative to handle the logistics of the expedition.

A space pioneer who directed surface photography for the Viking 1 space probe on Mars, Mutch never abandoned old-fashioned exploration — mountaineering — his whole life.

“I never knew if he was in outer space or there with us at the moment,” said John Braman ’77, a member of the first expedition. “Or in both places at once.”

Expedition 1: Against the elements

The Nanda Devi and the two peaks of Devistan I and II stand at more than 25,000 feet and 21,000 feet, respectively. These giants lie within a near insurmountable halo of alpine crests, 12 of which exceed 21,000 feet.

Only one passage exists to the sanctuary of Nanda Devi that would serve as the expedition’s base camp: a narrow, treacherous river canyon called the Rishi Gorge.

Hundreds of local porters,boxes roped to their backs, had lashed together trees and logs into a bridge several feet above the river.

Spring had just come to the Himalayas when the Brown group set out on the first expedition in 1978. The glacial melt surged into a torrential river that rose each hour, Moore said. The noise was deafening. “It was a race against time,” she said.

A few members of the 33-person party had been delayed in Delhi. Among them were Moore and Paul Palatt, a biology research assistant.

Eager to rejoin the others, Palatt went on alone. But as he stepped to the center of the river, a wave flooded the bridge and swept him away.

Minutes later, Moore arrived at the gorge to see the bridge had washed out completely. She learned that Palatt had been carried away into the river from Czech climbers who saw him lose his footing. She sprinted down the river to find him. She found a 100-foot waterfall.

A runner caught up with the group in a meadow high above the gorge to deliver the news.

Palatt’s body was never recovered.

Mutch, whose father was a preacher, held a memorial service for Palatt. They remained in the meadow for days, grappling with the loss. But they unanimously decided to carry on.

Above 12,000 feet on Devistan, rocks and glaciers pockmarked with deep crevasses suffocate all vegetation. Everyone split into small teams to approach the peak.

Wheeler remembers taking four to six breaths before each step. “The altitude was really surprising,” she said. “How tired you would be. How deformed your body got — swollen and burnt.”

Twenty-four members of the expedition reached the peak, a success.

Wheeler and Moore climbed the summit of Devistan with two other women, the only all-female team on the expedition. They sat there for an hour, facing the panorama of the colossal mountain of Nanda Devi shooting up out of the foothills. “It blew you away,” Wheeler said.

They buried Palatt’s wool cap at the summit.

Wildflowers greeted the weary climbers upon their return to the sanctuary. “We had come from a world of ice and rock,” Moore said. “It was like we were coming back to life.”

Expedition 2: In thin air

A decade after one of his early climbs in the Himalayas, a young Mutch found out he did not actually reach the summit. He had stopped at an illusory peak. “It pushed him to want to go back,” Binet said.

So in 1980, Mutch led a second expedition of six other members — among them Binet, Heimark and Nat Siddall ’82 — of the Devistan trek, serious mountaineers who wanted to tackle a more ambitious mountain, said Siddall, a member of both expeditions. They chose Mount Nun, all 7,135 meters of it.

Heimark, Binet and Mutch were the first to make the summit push.

They reached the summit on a clear, frigid day. Binet cried with joy. “It was the best half-hour of my entire life, to see we were the highest in the horizon, the clouds below us,” he said.

But most mountaineering accidents happen on the way down, Heimark said.

Mutch faltered while descending, dragging Heimark and Binet down the mountain for hundreds of meters. When they stopped, Mutch was concussed, his glasses torn from his face during the plunge. So they chipped out the ledge and waited, marooned in a world of white.

Mutch had lost one of his crampons, metal-spiked devices necessary to climb ice. After a brief consultation, Heimark and Binet secured Mutch to the ledge and returned to camp for spares.

Binet climbed back up to the ledge alone. Only the steel of Mutch’s ice axe glinted from the ledge where he once sat. Binet called out in the stillness. He saw a trail in the powder and followed it to an overhang. No sign of Mutch.

Night came quickly. Binet decided to stay at the ledge. His only meal — a can of tuna fish — had frozen solid, so he ate M&Ms, occasionally shouting Mutch’s name in the quiet gloom. “Maybe he would wander back,” Binet remembered hoping.

In the morning, a haggard Binet realized he had to return. During his descent, his sleeping bag slipped out of its pouch and tumbled down the mountain.

“It was another thing sliding out of my life,” Binet said. “I thought, ‘I could just go to sleep here and not wake up. Why should I go on?’”

But after a few moments he knew. “I’m not ready to die,” Binet remembered thinking. “So I got back up and continued down to Craig.”

Binet’s feet had flushed an ashen gray overnight from frostbite. They needed to leave, and soon. But first they built a cairn for Mutch.

Siddall and another member abandoned camp to search when the summit party failed to return. They encountered two figures “like zombies, shambling along,” Siddall said. It was Heimark and Binet.

They all huddled together in one of the two tents they had set up days before. The men sat in silence, speaking only about Mutch and the logistics of returning to base camp. It snowed all night.

They descended in one day the summit they took four days to climb.

Mutch remembered

A year after his death, NASA renamed the Viking 1 lander the “Thomas A. Mutch Memorial Station.” A crater on Mars bears his name. A plaque remembering Mutch will accompany the lander when humans first set foot on Mars.

“I would just sit and think about how lucky I was to be alive,” Binet said after the second expedition.

While some members would mountaineer for years following, others never climbed again. But for many, the first expedition to Devistan was a lifelong dream realized, Peters said.

Since 1978, most of the climbers — professors, classmates and former best friends — have lost contact. But during this Commencement Week, 25 of the 33 members of first Brown expedition will reunite in Providence 35 years after it occurred.

For the anniversary, Moore, who leads the Google Earth Outreach program, designed a virtual model of the first expedition that matches photos from the trek to real locations.

But reconnecting the members of the expedition will be the primary concern, Peters said.

“How many people get to have an experience like that?” Wheeler said. “To have your life feel so meaningful, so young.”

“It’s with me forever and all the time,” said Binet, whose 10 toes were amputated from frostbite.

When Binet and his wife moved into their first apartment, the first thing they hung on their wall was the photo of Binet, Heimark and Mutch at the summit of Nun.

It’s still there, with a quote from T.S. Eliot. “Only those who will risk going too far can possibly find out how far they can go.”

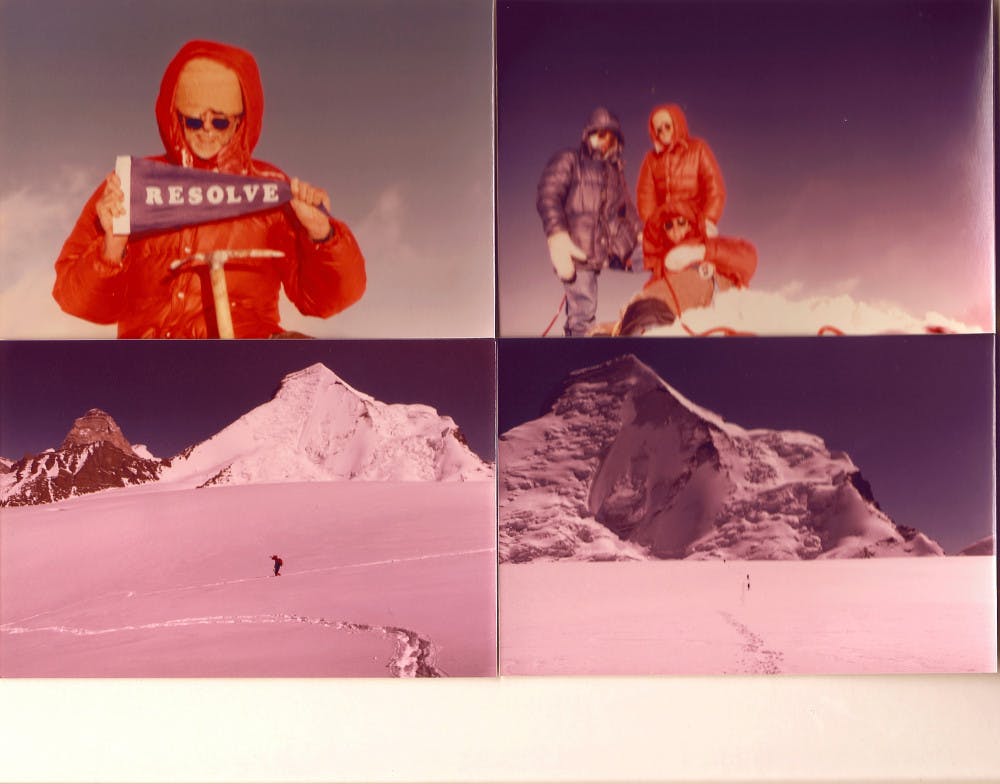

[caption id="attachment_2807547" align="alignnone" width="300"] [/media-credit] Mutch, in red, embarked with alums Binet and Heimark to climb Mount Nun, a Himalayan peak.[/caption]

[/media-credit] Mutch, in red, embarked with alums Binet and Heimark to climb Mount Nun, a Himalayan peak.[/caption]